You’re scrolling through your social media feed, making your way to your recommended content. A specific video pops up, where the creator describes a list of symptoms that leads them to conclude they have depression. The weird thing is, those symptoms sound a lot like things you experience every day. But you don’t know who this person is, whether they are right, or what you’re supposed to do now.

You scroll to the next video, but the implications of what you just saw linger in your mind.

This type of experience on social media is common, especially amongst active users. There’s always certain content that has to be consumed carefully, such as posts about diet culture or parenting. A wide variety of conflicting opinions and harmful behaviors that get passed on as fact are detrimental to unaware users, and the same pattern presents itself with mental illnesses.

That’s not to say that the vast amount of information on social media doesn’t have its positives. On the Internet, people are much more comfortable sharing their experiences with one another, and have often created online forums where they can foster a sense of belonging. They can find encouragement to overcome their personal struggles and finally receive validation for what they have been experiencing all along. But where does the other shoe drop?

The problem with much content about mental illness is that it quickly becomes a numbers game to gain a significant following on social media platforms. These kinds of accounts have been rising in popularity in the last few years, and other users have been quick to produce similar content.

This rat race directly leads to the promotion of unreliable and misleading information, and content where creators exaggerate their own experiences to make it appear as if they have a mental illness so they can receive more views. This takes away attention and validity from those who are genuinely trying to spread awareness about mental health. Moreover, unsuspecting content viewers may empathize through having had similar symptoms, and this starts a wave of people incorrectly labeling themselves as facing mental health issues.

This wouldn’t be as big of a problem if it weren’t for the rapid speed of information dispersal nowadays — content is disseminated so quickly that there is no time for it to be saturated amidst the public and for anyone to thoughtfully reflect on the information they are consuming. To address this, some might suggest enforcing an age restriction, limiting younger individuals from viewing and consuming this type of content. However, it doesn’t feel fair to ostracize the kids who may be looking for some reassurance online. In fact, it defies one of the main purposes of social media — our goal is to use these platforms wisely, not to exclude communities who benefit from them. It also becomes difficult to draw a line between those who have been professionally diagnosed compared to those who are self-diagnosed without invalidating anyone’s experiences and struggles.

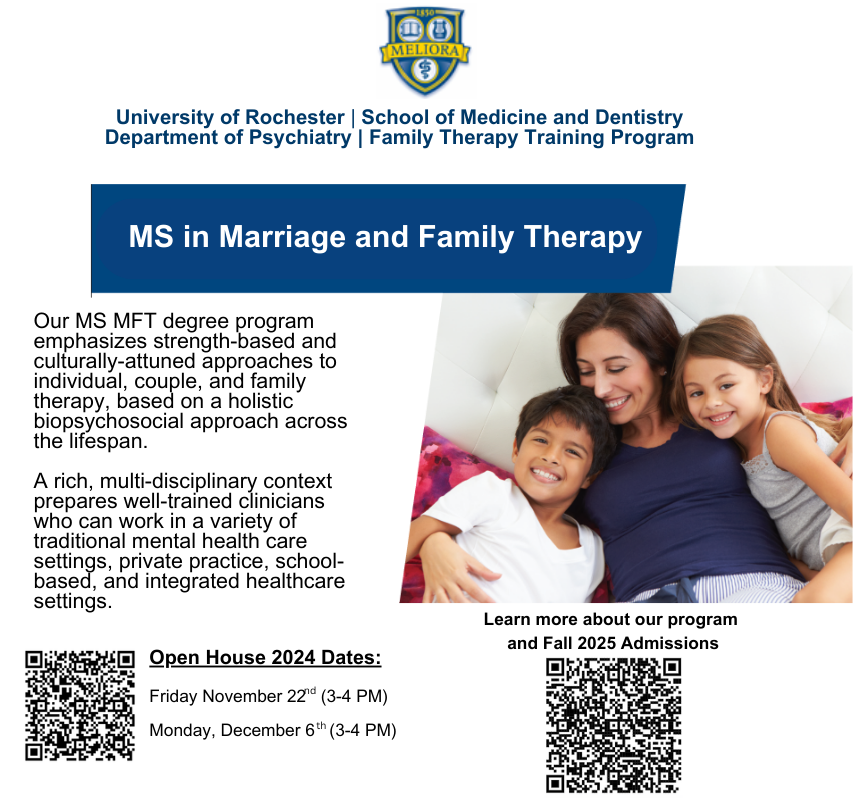

The best solution is to better educate oneself before jumping to any conclusions or taking any action based on ill-informed advice. That way, people can really reflect on whether they are assuming certain traits and symptoms because they saw them online, or if these symptoms have always been a part of their daily life. Together, smartly consuming media and responsibly creating content prevent misinformation from achieving a popular platform and spreading rhetoric that is potentially harmful.

It all boils down to the fact that people have to stop blindly consuming online content. For those who are too young to make that judgment, less-biased content should be promoted. Information from professionals rather than random users with a platform should be seen first. The goal shouldn’t be to discourage people from posting their experiences or going on social media, but to curb how much of that content shows up without precedent, as well as to restrict blatantly false information.