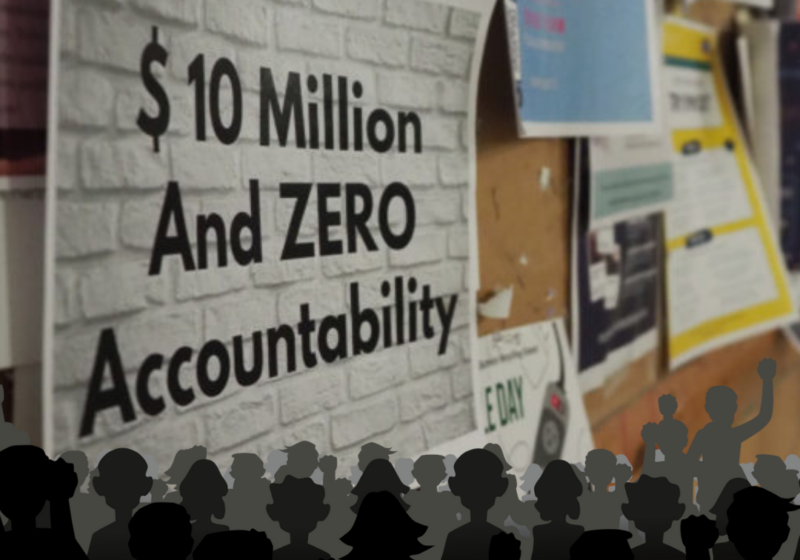

As many may have already known, during Meliora Weekend, students protested over UR’s lack of accountability and transparency regarding sexual assault cases. Over the few weeks since then, I have been reflecting on participating in my first protest.

When I first heard about the protest from my friend, I felt hesitant to attend, especially as an international student. Although America is a democratic country with a constitution protecting the freedoms of speech and protest, anxious “what ifs” immediately popped into my head alongside the news.

“What if I get kicked out of school?”

“What if my visa gets revoked?”

Moreover, I felt awful about disrupting a celebration held for alumni. Do I have the right to disrupt their return to their university? Would anyone care?

Yet, another part of me was excited. My first protest, the first step of becoming more socially and politically active, in a school thousands of miles away from home.

The main protest entailed walking around Wilson Quad, where a large group of people had gathered. As we walked, our paper and cardboard posters in hand, I felt people’s stares. Under my mask, I could feel the heat of anxiety as my thoughts raced again:

“Why am I doing this?”

“I want to leave.”

“This is embarrassing.”

Then, some people in our group began to chant. After a moment of hesitation, I joined, turning my frustrations at myself, at my experiences with sexual assault, and at the world into rough, ugly shouts. My brain nearly forgot that I was rallying with a group of people behind the same cause, but once I heard the echoes of our voices I felt empowered to scream freely. The stares lost their fear-inducing power. Instead, they became motivational — a sign that we were getting attention. At one point, I even overheard an alumni thanking us for holding this protest, for never letting this issue die down. By the end, even though my throat couldn’t handle shouting anymore, I felt accomplished.

The power and importance of protests comes from our ability to turn what is impossible as an individual into power as a group. No matter how pressing an issue is, nothing can be done alone. This is probably obvious. However, a key part of this day had yet to come, one that would take a bit of my pride away.

On our way to the Wilson Quad, we saw a figure in the distance. One of the protesters said, “That’s President Mangelsdorf!” Confusion rippled through the crowd as most of the group continued to move towards the quad while some hesitated. Those behind, including myself, were told — rather, shouted at — to chase after the president. Caught in the heat of the moment, amidst those shouting voices, I followed. I ran after the disappearing figure for minutes until she eventually disappeared inside a building. I later learned that she was trying to ignore and get away from us.

We were warned afterwards, when the protest was over, about how harmful that could have been. What was meant to be a peaceful protest very easily and quickly became harassment. I still feel the burning sting of shame and regret for chasing after a woman who, before seeing us, was probably having a normal day. Passion for a cause is important, but there is a right way to channel and use it — this was not one of them.

What was the most shocking and, truthfully speaking, frightening thing about that moment was how instantaneously I lost my ability to think independently. How I didn’t question the moral implications of my actions. The combination of nerves and emotions, looking for any opportunity to release itself, latched onto anyone with power and authority. Those who spoke the loudest, took the daring actions, exuded confidence were, in my simple brain, the ones I should follow, not the sensible individuals who organized the protest. I understand now how easy it is to lose your mind. To act without thinking.

Protests, like my high school political science teacher once said, are like valves of a pressure cooker. They are tools by which citizens can let their frustrations be known to authorities instigating action with noise and disruption. However, much like those valves, one must be careful in their use, lest you hurt yourself. During the heat of the moment, when emotions and pressure are high, there is a high chance we will take actions we will regret. Instead of being a peaceful protest, it can derail into harassment, or worse, violence.

I am not saying protests are wrong. In fact, after this experience, I understand even more the important role protests play in a democratic society. I am, however, sharing my ideas and experiences to caution everyone, myself included, to practice critical thinking. To cement it so hard into your mind that, even during times of intense emotion, you never lose your head.