I find it funny when people automatically assume that because I’m Asian, I’m good at math, play piano or violin, or study like a robot. I mean, I am good at math. I do play the violin. I did play piano, at least for a couple years. My study habits aren’t terrible but aren’t superb either, and I’ve had my fair share of cramming assignments last-minute like everybody else. I’m a minority, but perhaps as a result of some of these stereotypes, employers don’t see my skin color as “one of the troublesome ones” they should avoid. Store owners don’t follow me around the shop, because I don’t fit the image they have in their mind of a shoplifter.

Although these assumptions may seem beneficial or even flattering, these academic instances of “false privilege” are growing more tiring, while the latter examples reveal themselves to be much more problematic.

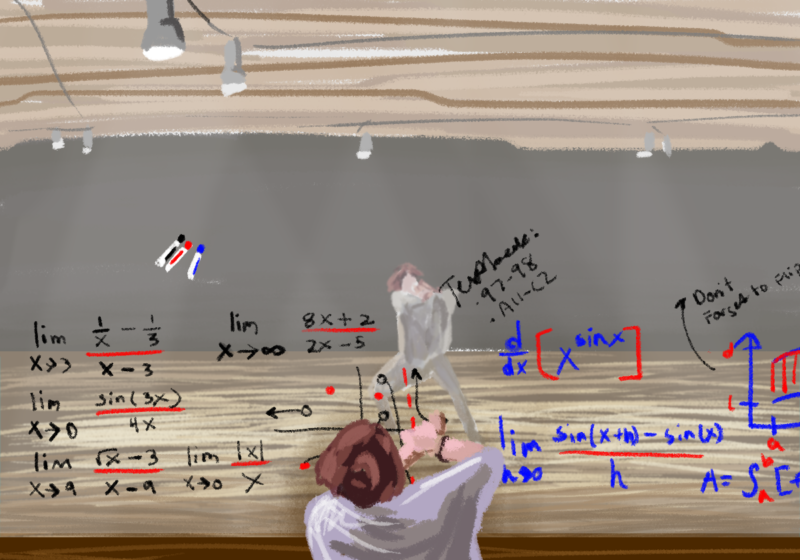

I myself had never quite actively contemplated the racial privilege the myth grants me — as well as its burden — until a couple years ago; admittedly, few consciously realize their privilege until it’s called into question and consequently threatened. My last few years of highschool, I repeatedly had to list out my achievements in preparation for college applications. In this process, I realized that my academic and extracurricular achievements fit almost-perfectly within the standards set for every other Asian-American 17-year-old. It made me feel superficial and hollow. As the application process neared, I even began to view myself like the typical cookie-cutter Asian-American student with the same hobbies and interests — “they’re all the same, anyway!” — and worried I wasn’t doing enough to stand out. How do you embrace yourself entirely with respect to your racial identity and individuality when you do fit the stereotype?

Reflecting on my own experiences, I’d like to explicitly clarify that my passion for playing the violin and initiative to try piano were my own decisions and not dictated by my Asian parents. Unfortunately, I feel the need to consciously state this whenever I tell someone new about my hobbies, which points to the model minority myth’s racist effects on the everyday person’s mindset. Ultimately, the truth is that my perspective and choices that happen to align with Asian stereotypes have not been, and will not be, free from cultural pressure, but this never justifies why I have to constantly prove that I’m not just what everyone assumes an Asian-American to be — that I’m more than just a stereotype.

The desire to fit in within my racial community and maintain a comfortable place in a broader white society seems to require a constant wariness in rebutting stereotypes, or a forced compromise of some aspects of my own racial identity to stand out against my peers. As we exercise and sacrifice different parts of our identity to better belong in majority communities, our racial identity develops in harmony and resistance to these environments, perpetually — and perhaps unfortunately — stuck between conformity and hyper-visibility.