“College kids are online because their friends are online, and if one domino goes, the other dominoes go,” Mark Zuckerburg’s character quips in The Social Network, a 2010 movie about Zuckerburg’s origin story.

Back in 2004, the dingy little man launched Facebook and revolutionized the way the average person interacts with and portrays themselves on the internet. People have always followed social trends, but with the emergence of the internet first in peoples homes, and then their pockets, this jumping-on-the-bandwagon mentality has only amplified.

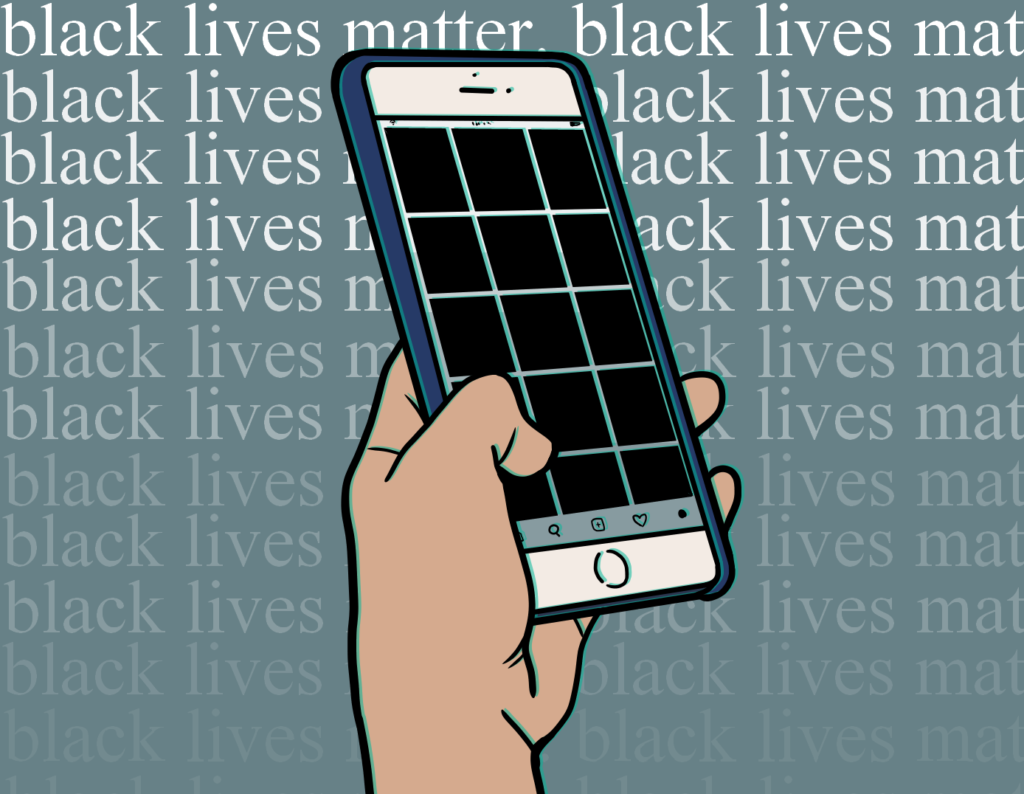

It’s no surprise, then, that last Tuesday, all platforms (but mostly Instagram) were flooded by completely black screens in compliance with #BlackOutTuesday.

The creators of the movement, Jamila Thomas and Brianna Agyegman, explained that Black Out Tuesday began in the wake of George Floyd’s murder as a tag called #TheShowMustBePaused. On their website, the two artists declared that June 2 would be a day of disruption in the music industry. Their intention was to “hold the industry at large, including major corporations + their partners who benefit from the efforts, struggles, and successes of Black people accountable.”

That day, big stars in the music world started postingBlack squares on their Instagram with this tag. But as it quickly spread, the tag transformed to #BlackOutTuesday. Then, as the movement shifted to other artists and later to the general public, some began tagging their Black screens with #BlackLivesMatter.

Currently, social media is flooded with posts about how you can help by being a better activist and ally, many of which are tagged #BlackLivesMatter. By captioning blank, informationless squares with #BlackLivesMatter, social media users clogged a tag that aims to be a space of organized information with nothing but a dark, blank screen.

Additionally, a social media Black Out doesn’t mean that all users post a black screen in solidarity. It means that white people take a step back from their respective platforms so that they can become a space for Black people to express their thoughts, feelings, and perspectives. White people aren’t supposed to turn off their notifications for the day, but rather stop posting their own opinions in favor of resposting and uplifting Black voices and perspectives.

BlackOutTuesday was only one day, and the tag’s already recovered, but that’s not the point. The mistagging of #BlackOutTuesday alludes to a larger problem with white Americans.

The current protests are unfolding as the COVID-19 pandemic continues its course through the United States. During quarantine, people clung to social media to facilitate emotional connection, since physical connection was scarce.

A few weeks ago, I was being tagged in those “draw an orange” challenges, where people drew a picture of the fruit, tagged their friends, and encouraged them to keep up the trend. A few days ago, people I knew were posting the phrase “Black Lives Matter” to their stories, tagging a few friends, and encouraging them to spread the message.

Although it’s important to bring people’s attention to the Black Lives Matter movement, I can’t help but feel as if these two reposts are linked. In that particular instance, similar to the quarantine orange challenge, white Instagram users were screenshotting the story in which they had been tagged and reposting it. They were turning a movement into a trend, wiping their brow, and setting their phones down for the day.

Aside from forwarded email chains, the first internet trend I clearly remember was the ALS Ice Bucket challenge. In 2014, if someone tagged you in a video of them dumping ice water over their head, you responded with a video of you doing the same, even if you weren’t aware of the fact that the challenge was intended to spread awareness of ALS disease — otherwise, you were breaking the trend.

But the viral spread of the ice bucket challenge resulted in a $115 million dollar spike in donations for ALS research. How? Because many consumers of the challenge didn’t stop there. They researched, donated money, and contributed to the cause. Similarly, posting the phrase “Black Lives Matter” on your story and calling it quits doesn’t do much for the movement other than spread awareness of its name. Awareness is great, but on its own, it’s performative and shallow. It feels especially performative when these posts show up next to other ones spreading information about how to contribute to the movement beyond this simple action.

The internet has proven to us that if one domino goes, the others go, too. By educating yourself and spreading access to resources about the Black Lives Matter movement and how to help, hopefully you knock down a few stubborn dominoes that refuse to budge. Spreading awareness isn’t enough anymore. We’re no longer 14, as we were when the ice bucket challenge was popular. We can do more. Read the articles, posts, books, and documents people have been spreading like wildfire. Sign petitions. Call your local officials and representatives. Talk to your family. Nothing worth doing was ever easy. In times of crisis, social media has revealed itself both to be a menace and a resource. What will it be for you?