Have you ever felt a pair of eyes watching you while you wander the tunnels at night? Or heard footsteps while studying in the stacks, even though you’re alone?

You may have just felt the phantom presence of Pete Nicosia, a ghost who’s appeared in supernatural reports over the decades.

The story begins in the late 1920s with the construction of Rush Rhees Library. Nicosia, a mason’s helper and recent immigrant from Sicily, was handling a wheelbarrow full of concrete on the highest levels, when the wheelbarrow slipped and started falling off the edge. Nicosia, a sturdy young man of 25, tried his best to hold it back, but failed.

When he let go of the heavy wheelbarrow, he stumbled backwards, hitting the edge of the scaffolding and tumbling over the guardrail to his death.

The foreman of the construction crew, James Conroy, signed his death certificate and paid for the funeral expenses out of Nicosia’s wages and savings. Some years passed by, the U.S. entered the Great Depression, Nazism rose in Germany, and Nicosia became history.

He didn’t remain that way.

In the fall of 1932, a junior named George Maloney was walking on Eastman quad on a foggy morning when he met a strange man outside of Morey Hall. The man, whom Maloney described as an “Italian fellow” wearing worker’s clothes, asked Maloney if he’d seen his boss, Conroy. Maloney denied knowing any Conroy and directed him to the office of Clarence Livingston, the Superintendent of Buildings and Grounds.

Over the next year, Maloney saw the man again, this time with his friend Joseph Stull in the tunnels below the library. Stull also met him by himself, during which time the Italian man “bummed” a cigarette off him.

The sightings came to a head in October 1933, when Maloney and Robert Metzdorf ’33 went to the top of Rush Rhees. They’d crawled up through the little window to the platform for some sightseeing, and they were met by the same man. After chatting, Maloney and Metzdorf prepared to leave. The Italian man inquired about the height of the tower, which Maloney told him was around 150 feet. The man said: “Oh boy, one hundred and fifty feet!”

When the two students went back down, they told librarian Donald B. Gilchrist about it. Gilchrist himself went to see the man, but he had disappeared. Apparently, Gilchrist told them, there were numerous accounts of a stranger on campus. Maloney relayed his experiences, including the man’s requests for Conroy, whom Gilchrist happened to know. Gilchrist promptly sent a letter to Conroy, describing the Italian man.

Conroy, assuming someone had given Gilchrist a description of a dead man, sent back a letter describing Nicosia’s fall.

This all could have been chalked up to an eerie case of doppelgangers, if it had not been for Maloney’s final run in with the man. This time, Maloney asked the man, “Say, do you know of anybody named Pete Nicosia?” The reply: “Shu,” the man chuckled, “that’s me, Pete Nicosia.”

And when Maloney asked about his fall: “That’s right,” he said. “One hundred and fifty feet […] It didn’t hurt one bit.”

At least, this was how the tale was told, in its original rendition by Maloney in the March 1934 edition of the Soapbox, the men’s literary magazine at UR.

The spectral story became a subject of controversy on campus quickly after, and throughout the decades. Numerous articles have been written about it, first in the Campus (predecessor of the Campus Times), then in CT itself, plus media outlets like UR’s online Newscenter and in a book about ghost stories in New York State.

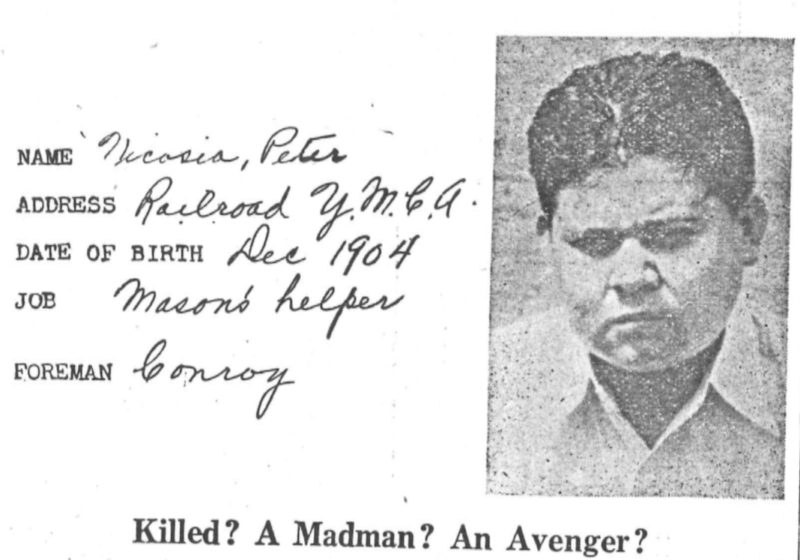

The March 1934 issue of the Campus — published soon after Maloney’s Soapbox article — featured Nicosia’s story on the front page with a picture of a document, supposedly Nicosia’s employee records as a mason’s helper for Conroy, which included a photograph of a man assumed to be Nicosia. The article wrote that Maloney and Metzdorf, upon seeing Nicosia’s photo, exclaimed that “either that’s the fellow or his twin brother.”

The Campus article also reported sightings by several other people, including professors, and said that Conroy’s letter detailing Nicosia’s death was “available for examination at any time in the Campus office.”

For skeptics, the prevailing theory was that the man was a relative of Nicosia, come for revenge.

Throughout the decades, further reports of sightings came up, some more sensationalistic than others, first in 1940, then again in 1948, with Bob Weiss’ first-person account in the Campus: “He’s come back! The restless spirit of Pete Nicosia has again been seen in the library.”

Weiss described how Nicosia appeared to him in the library basement and narrated his life, death, and afterlife, asking for Weiss (then Campus senior staff) to publish his story.

But, Weiss’ retelling of the story was inconsistent with earlier accounts, including a previously previously unpublished testimony by a man who allegedly saw Nicosia and ran out of the library yelling that he’d seen a ghost.

Weiss’ version was sensational, because it was made up.

In a 1990 article, CT reported that Weiss said in a telephone interview that his 1948 article was a figment of his imagination.

“I vaguely remember a story about a ghost rumbling around the library, but I can guarantee to you that I never saw it,” he said. “I think I would remember that.”

But the question remains: did Pete Nicosia exist, did he die, and did he come back to haunt Rush Rhees?

Melissa Mead, the archivist at the University, says that she has been unable to find records of Nicosia’s existence at UR, much less death by brutal fall. Though the “Big Book of New York Ghost Stories” by Cheri Revai described the Conroy letter, a key piece of evidence in the original claim, as being handwritten on the back of two time-cards, suggesting that the letter did exist at some point.

Articles from later decades report details the originals don’t have, or contradict, and build upon the legend of Pete Nicosia. Mythologized in his sporadic appearances, Nicosia was portrayed as a publicity-lover, a football hopeful, and an “incurable ham.”

The Newscenter reported that in 1985, Maloney wrote (source unnamed) that “the story of Pete Nicosia was inconclusive in 1934. At this late date, I expect that it will remain so.”

Perhaps George Maloney’s original account is true, and the records have been lost with time. Or perhaps his tale was a ploy to get more people to read the Soapbox magazine.

In 1934, the Soapbox was still in its earliest years. The key players of the Nicosia haunting in the 1930s were all involved with the publication. Maloney was a member of the Board of Editors for the Soapbox issue that published that first account. Gilchrist was the Faculty Advisor. Stull and Metzdorf had been on the Board of Editors in November of 1932, soon after the first alleged “sighting.”

Almost a century later, the mystery of Pete Nicosia remains.

A definitive answer to whether there was a ghost in Rush Rhees may never be attained, but if you happen to find a stocky, young Italian who asks for his boss in the stacks, you might want to ask his name.