When I was around 8 or 9, a college student who frequented our house told me to listen to my first podcast. “Listen to this while lying down in a quiet room with the lights off,” she told me. This was over a decade ago, the podcast was “Radiolab,” and I’ve been listening since.

Now, you can find a podcast on any subject or format you could think of. But the ones that I come back to again and again are the story ones. True ones, about strange people or phenomena, like “Radiolab” or “This American Life,” or fictional ones, like “Lore.”

Perhaps it’s the power of humanity’s long tradition of oral storytelling, or nostalgic echoes of a parent telling bedtime stories, or the dreamlike escapism of imagining lives and moments that aren’t yours , but there’s something wonderfully intimate about hearing someone else’s voice in your head as you live through their stories.

So, when the Rochester Fringe Festival lineup included the live show of a storytelling podcast called “The Memory Palace,” whose episodes had made Jad Abumrad, “Radiolab”creator, say “Goddamn, that was good,” I had to go.

“The Memory Palace” was created by Nate DiMeo in 2008, featuring little-known historical moments told vignette-style in literary, evocative prose.

The podcast is DiMeo’s voice over minimal music as he tells stories from the past.

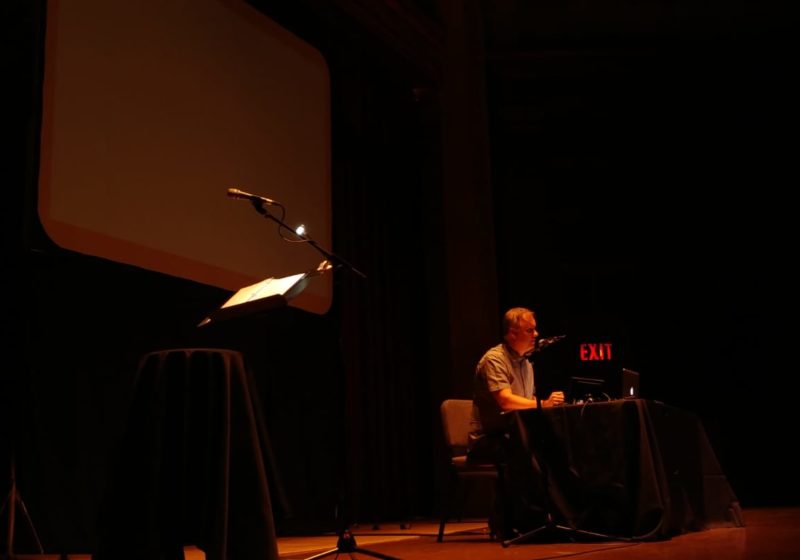

The live show is similarly intimate — just DiMeo on a stage with a computer, a projector screen, and some microphones in low lighting. Nothing extravagant or flashy, just eloquent and personal and sometimes funny, mirroring his stories.

Just listen to how he begins a story about the mass jailbreak by the animals at the Central Park Zoo: “The old woman kneeling at the altar in the flickering candlelight, lost in prayer, didn’t hear the bear pad into the church of St. Thomas. And so, her death, which came as the grizzly’s teeth sank into her throat — while horrible — was sudden, and swift, and therefore relatively merciful as these things go.”

Unlike his normal format, the live show allows DiMeo to expand the presentation. In the Central Park Zoo story, as he listed the newly freed animals, one after another, stop motion clips of those same animals appeared, one after another, walking steadily on the screen, their soft, felted appearance unthreatening compared to their murderous counterparts.

In a story about Soviet space dogs, a brass band of Eastman students provided the background music. Another story was about Florence Chadwick, a remarkable long-distance swimmer who grew up with the dream of swimming the English Channel and did just that at the age of 31.

Chadwick’s story is the one that DiMeo connects to the most, and also one that demonstrates what he looks for when developing a story.

The challenge of creating an episode is not finding the story ideas, DiMeo said in an interview with the Campus Times after the show.

“Literally you just have to go onto the internet for a little bit,” Dimeo said, adding later, “What I’m really looking for is the thing that turns an anecdote into a story, and for me that’s meaning.”

For the piece on Chadwick, at first, it was only an anecdote, but over time, a meaning emerged. It became a way to shed light on a reality of fame: “the way that sometimes you do a big thing, and you get a lot of attention for it, but then you have to keep going. Suddenly I start to find meaning in that little anecdote.”

As Dimeo said in the show, he was tempted to leave the audience in the moment when Florence swims across the English Channel for the first time, her “big thing,” but he doesn’t, because at that point, “she is 31, she will die at 77 in 1955 of leukemia in San Diego, and it will be too young. But there is so much life to live between [that] moment and the end. And though there will be no moment like [that] one — when the world first learns her name, when the dream she’s fulfilled is so pure and precise and easily understood and explained — there will be other moments and other dreams. There has to be, with that much more life left to live.”

The piece ends with Florence Chadwick in the ocean, at any of those moments when she is in the water. “Hips up, reaching out as far as she can. Right arm, breathe, left arm, right arm, breathe, left arm. And on and on, and onward and onward […]”

At the end of a particularly touching story, about a Zulu man named Mkano and an Italian immigrant named Anita Corsini, whose love was too strong for the taboo against interracial marriage, the racist imperialism that forced Mkano to perform as an exotic curiosity in a Brooklyn museum, DiMeo muses on the impossibility of fully capturing another person’s story.

“What can we know of their love? Some historians have done their best to know as best they could, tried to sift through the clues the couple left on the rare occasions that their lives would catch the light […] But we can’t know what they thought of each other. What they liked most. What they want to change […] These two people who found each other, when each was so far from home. We cannot know their love. We can just hold it up to the light for a moment, and then let it fade. And just note for a moment, how brave the thing is, to love anyone in this world.”

I wish I could retell all the stories of the show, like how Harriet Quimby dreamed of adventure and became the first American woman to get a pilot’s license, or how the Central Park Zoo story was actually a hoax, or how Soviet dogs went to space.

If I could have, this article would have just been a video of the show itself, so that you could see and hear for yourself what mere words on paper cannot describe, but that isn’t my job. The best I can do is to tell you what I felt, and to tell you to go listen to “The Memory Palace” while lying down in a quiet room with the lights off.