In front of Rochester’s City Council on April 16, Phyllis Harmon tearfully opened her neck brace, showing what she says are the remnants of eight screws and a plate that had to be put in.

“If you all don’t do nothing else today, think about me,” she shouted. “Me! And get this right.”

Harmon sustained her neck injuries, she says, in an assault by two Rochester Police Department officers.

She is one of many who believe Rochester needs a police accountability board. But others, like Rochester’s police union, believe the board would compromise officers’ ability to keep citizens, or themselves, safe. As the City Council vote nears, questions over who gets to hold power and who gets to feel safe persist.

___

According to City Council’s most recent draft of the legislation, the board would have investigative, subpoena, and disciplinary power over claims of police misconduct, as well as power to examine RPD policy. It would be independent of city government or RPD.

The legislation would allow former law enforcement officers — not from RPD — on the board. The Mayor would nominate one member, and City Council and the Police Accountability Board Alliance, an advocacy coalition, would each nominate four.

Ted Forsyth, an Alliance leader, co-wrote an April 2017 report with fellow activist Barbara Lacker-Ware recommending a police accountability board.

Later that month, City Newspaper reported that City Council president Loretta Scott was interested in police oversight reform.

According to Stanley Martin, an Alliance leader, there had been past pushes for police accountability boards, but that report spurred this current initiative.

Adam Devincentis, the secretary of Rochester’s police union, said City Council’s proposal is based on the report, which he said is “filled with lies.”

City Newspaper attributed City Council’s interest to Ricky Bryant, a teenager who claims he was attacked by police in 2016. The city settled with Bryant, who received monetary compensation.

A September 2017 report ordered by City Council from the Center for Governmental Research, a nonprofit consultancy, says the rate of use-of-force allegations sustained by the police chief in Rochester from 2003 to 2016 is three percent.

Forsyth’s activism on the issue began, he said, with the case of Benny Warr who was arrested, pushed from his wheelchair, and beaten by police in 2013. The city said Warr’s resistance merited use of force.

In February, Warr was awarded a dollar in his wrongful arrest and excessive force lawsuit.

Forsyth said he began spending his time supporting people like Warr by working with lawyers, making public statements, and obtaining evidence. But he felt stuck.

“I could put up a hundred horrible interviews or horrible video depictions of police violence in Rochester, and it doesn’t seem like it’s having any effect,” he recalled.

Forsyth said he and Lacker-Ware attended meetings with the United Christian Leadership Ministry, a community-focused Christian organization, where attendees laid groundwork for the proposal.

The journey hasn’t been simple. After City Council released a draft of the legislation in September 2018, Mayor Lovely Warren released her own in December, proposing to keep disciplinary power with the police chief.

But City Council held Warren’s draft in committee, barring it from being up for vote. If City Council pass any legislation on this board, it will be their own.

But it still faces challenges.

Many oppose allowing former officers on the board. And granting disciplinary power to the board means taking it from the police chief. To change who has disciplinary power, citizens must vote to change the City Charter. That vote will happen in November.

___

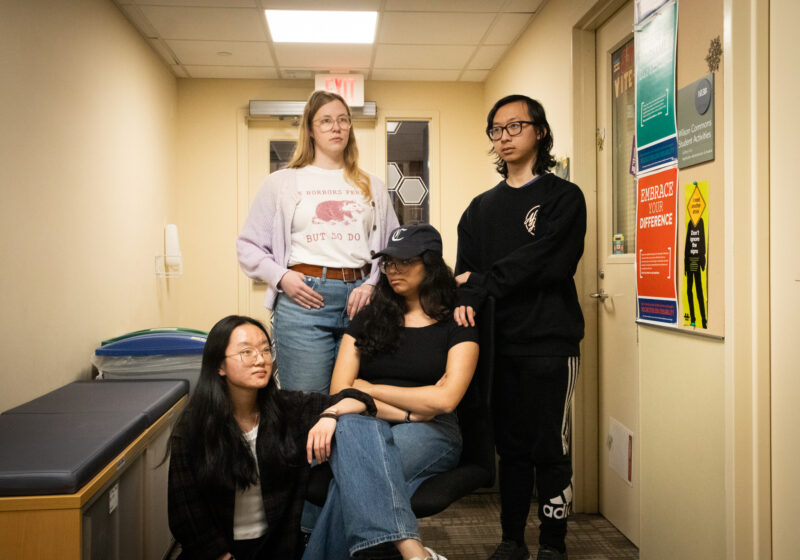

Martin, now a City Council candidate, came to Rochester in 2014 as a UR grad student. She lived off campus her first year, where she said she noticed mistrust surrounding police.

She spoke of Silvon Simmons, who was shot three times by an officer, running from a police cruiser that was following the car he was in. The officer said Simmons shot at him first. Simmons was later cleared of all criminal charges, and is now suing the city. His parents are Alliance members, Martin said.

Adding a retired officer to the board, Martin said, would hurt its mission.

“That presence, for some, really is a sense of oppression, it’s a sense of abuse,” she said.

Martin said the change came through City Council’s communication with Rochester’s police union — the Locust Club — whose representatives spoke at the March public City Council session.

One of those representatives was Devincentis.

Locust Club secretary and RPD sergeant Adam Devincentis, next to a memorial to slain RPD officer Daryl Pierson, at the Locust Club office.

An RPD sergeant, Devincentis told the Campus Times that discussion on the proposal ignores the safety of officers, citing Daryl Pierson, an officer slain in 2014.

“When I’m working on the road, […] I’m leaving a wife and kids,” he said. “I don’t know what’s going to happen. Daryl didn’t know what was going to happen that day, but that is a reality that we face.”

Months after Pierson was fatally shot by a man he was chasing, the Locust Club contributed to a donation of $15,000 and a new car for his widow.

A lack of understanding causes many of RPD’s perception problems, Devincentis said.

He gave the example of an individual, who — according to Forsyth and Lacker-Ware’s report — was Tasered and beaten so badly he lost an eye, and was awarded monetary compensation in the resulting lawsuit. Devincentis said the individual was drinking while driving, nearly hit an officer, and violently resisted arrest, and that his eye was “dead” before the incident.

Devincentis said excluding law enforcement from the board would make it “stacked against police officers.”

“This group [of board advocates], for lack of a better term, is very just anti-police,” he said. “They’re not pro-community.”

___

In an interview with her fiance and daughter, Harmon told the Campus Times that, on July 14, 2013, after she repeatedly asked two RPD officers to leave her home, one grabbed her head and put it between his legs, laughing.

“The other officer was looking under my shirt,” Harmon said, tearing up. “It just made me feel so defeated.”

Harmon said the officer then slammed her into her door and pepper sprayed her.

“I couldn’t breathe because I have asthma,” Harmon said.

She said the same officer body-slammed her to the ground. The other officer, Harmon said, kicked and beat her before kneeing her in the back and arm. Then she was arrested and put in a police car, she said.

The officers’ reports and a statement from a witnessing contractor say Harmon approached one officer standing in front of her doorway — despite being told to stop — and hit him in the chest. The documents say Harmon was pulling away from the officer as he tried to grab her arm to cuff her.

Then one officer pepper-sprayed Harmon, the reports say, before she was pulled to the ground and handcuffed.

The reports said that Harmon was brought to the psychiatric section of Strong Memorial Hospital. She was charged with obstructing governmental administration and resisting arrest. Harmon said the charges were dropped.

When asked about the incident, Devincentis denied Harmon’s accusations.

He also said that Harmon’s lawsuit mentioned nothing about being grabbed by the head as she told CT. Legal documentation Devincentis provided supported this.

Nearly six years after the incident, Harmon’s lawsuit against the city of Rochester is ongoing.

___

The City Council vote — the proposal’s next hurdle — will be held on May 21.

Editor’s Note (7/28/19): The name of the individual, who Devincentis named as an example of a lack of understanding of use-of-force incidents, was removed, because the individual was not contacted for their account of the incident.

Editor’s Note (5/27/19): A comment made by Devincentis regarding Harmon’s claims was removed as Harmon was not given the chance to respond before publication.