After a December 2016 night of heavy drinking and smoking, Morena Heyden ‘17 awoke in her bed to find her friend from RIT standing over her.

He had texted earlier, wanting to see her. She had told him not to come.

She signed to the student, a deaf man: How did you find me? He signed back that he had spotted the name tag on her door. He told her he’d been dropped off by a friend, and not wanting to leave him stranded, she invited him to sleep beside her.

“I only remember bits and pieces — him making out with me, moving me around, things like that,” she told the Campus Times in an interview this past fall. “It was so hard trying to put together those pieces to tell campus security to fill out those forms. I was on drugs that night. I can only extrapolate what I can from the vague memories that I have.”

Heyden woke up the next morning terrified. She had gone to sleep in leggings, a camisole, and underwear, but only her camisole remained. Her friend lay in boxers. In a panic, she sought out two fellow residents of the Music Interest Floor — where she had never seen a reason to lock her door — and asked them to talk to the RIT student.

Using pen and paper, one of them asked him if Heyden had consented.

“She didn’t say no,” he wrote, a frown on his face.

That morning marked the start of a downward spiral for Heyden, who recalled, on top of grappling with her trauma, feeling blamed and abandoned as she tried to navigate between UR’s and RIT’s processes. At the end of it all came the news that the RIT student hadn’t violated any of that school’s policies.

Discomfort with Public Safety

That morning Heyden called Public Safety, and she and the RIT student were interviewed separately by investigators. Then she got a rape kit done at Strong Memorial Hospital.

“I had a great sense of humor the day after,” she said. “But it was interesting because it just kind of plummeted after the hospital. It hurt like hell when they examined. It hurt so bad I was crying.”

Even though the RIT student had been banned from campus, Heyden couldn’t sleep in her bed for two weeks, she said, and afterward even began sleeping in the opposite direction.

After deciding to take a medical leave the following semester, Heyden in January filled out a proxy report, an anonymous form used to disclose incidents to UR’s Title IX office.

Later that month, she said she was interviewed by Lorraine Strem, another member of Public Safety’s investigations unit. Heyden felt victim-blamed by Strem and uncomfortable with her questioning. She said the investigator gave her advice she didn’t need, telling her what she could have done.

“‘Now you know you didn’t have to let him in,’” Heyden recalled Strem saying.

Strem did not respond to a request for comment.

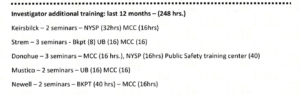

According to a document obtained by the Campus Times detailing Public Safety’s sexual assault training, in the past 12 months, Strem has attended three seminars for a total of 40 hours at SUNY Brockport, Monroe Community College, and the University at Buffalo.

Public Safety sent evidence from the case to its RIT counterpart, and Heyden received an email from RIT’s Center for Student Conduct and Conflict Resolution, asking if she’d be willing to Skype in for a hearing at the end of February. She agreed to the hearing due to convenience, as she had been taking her leave of absence in the Syracuse area.

“I was more focused on getting my thoughts out there, not breaking, and trying to get it done, get closure,” she told the Campus Times.

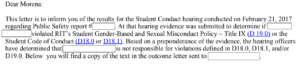

A few days later, she received a letter email from Joe Johnston, the RIT center’s director. The letter revealed the results of the hearing: The accused hadn’t violated that school’s Student Gender-Based and Sexual Misconduct Policy or its code of conduct. The decision did include a no-contact order, though.

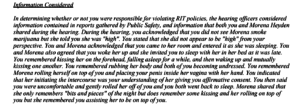

The letter revealed the information the panel considered: The accused didn’t see Heyden smoke marijuana, but she had told him she was high, which he said he saw no sign of. He told the panel Heyden had rolled herself on top of him and guided his penis inside her vagina, but that after intercourse had begun he became uncomfortable and ended the encounter.

RIT’s sexual misconduct policy describes consent in this way: “A person shall not knowingly take advantage of another person who has an intellectual or physical disability, who is incapacitated by prescribed medication, alcohol or other chemical drugs, or who is not conscious or awake, and thus is not able to give consent as defined above. Silence or lack of resistance, in and of itself, does not demonstrate consent.”

RIT’s policy also outlines what a complainant must receive in the decision letter following the hearing. The “Notice of Outcome” must include “information regarding the appeal process,” a piece of information excluded from Heyden’s letter.

Heyden said neither UR nor RIT provided her with information regarding an appeals process.

“I feel really abandoned, like UR and RIT just brushed me aside,” she wrote in a message to the Campus Times. “I’m pissed, but also feel hopeless at the same time because if they didn’t bother to tell me I could appeal, what are the chances that hearing would have been any different?”

A second hearing might have been difficult for Heyden, but she saw its benefits: “Although I may have to see my rapist, I would feel more in control than through a Skype camera, and would know what to expect.”

An RIT spokesperson declined to comment on the situation, citing confidentiality.

A UR spokesperson, who was also responding on behalf of Strem and Levy, did not comment on Heyden’s situation but detailed the University’s process for addressing sexual misconduct cases involving a non-UR student. The spokesperson also provided UR’s “updated guide to reporting a case of sexual assault, as well as the services provided to students.”

‘I’m sick all the time’

After the receiving the decision letter in February 2017, Heyden received an email from UR Title IX coordinator Morgan Levy email detailing the steps she could take, which included going to the police. Heyden told the Campus Times that she could not report the incident to the police during her medical leave because the incident had occurred outside her home county.

Heyden said she and Levy played phone-tag until she had become too busy to continue pursuing Levy’s guidance.

Levy did not comment on Heyden’s case.

In an email Levy sent the Campus Times prior to the reporting done for this article, she explained what her role is as the Title IX coordinator.

“I can and do inform students of their rights and help them think about what they want to do next and assist them in getting what they might need to do that. Hopefully through these steps I can create a path the student can use to begin to heal, find support and get closure, but I will never be able to undo the awful thing that brought someone to my office,” she wrote. “I can refer students to counselors, but I am not a counselor or a therapist. I also do not investigate allegations of sexual misconduct or make decisions about whether the policy was violated, but I can connect students to those that do investigate and adjudicate it.”

“I wish they had been more supportive throughout the entire ordeal,” she said. “In hindsight I could’ve asked much better questions about where things were going with the report, but you don’t think about things like that right after trauma. You don’t think about those pertinent questions.”

Heyden believes that Restore’s office hours on campus are necessary, but wishes that they had been mentioned during the process: “I like that Restore has office hours on campus, and wish someone would have given me their contact instead of stupid stickers on the back of mirrors.”

People who would have connected her with better resources would have been helpful, she said.

“It might be a lack of empathy combined with the fact that it’s a 9-5 job for them,“ Heyden said. “You get people who go into a job where they don’t have the right tools to start out with emotionally, and you need to provide them with what they need to be able to fulfill their duties really well.”

Heyden said she told her story because she wants to make a difference.

“I want rapes to be less underreported than they are. I think about it and I get sick,” she said. “I’m sick all the time.”