Would you feel safer on campus if Department of Public Safety (DPS) officers had guns?

For many vocal students, the answer is no.

That much has become clear in the past two weeks, as the possibility of equipping some DPS officers with firearms was met with fierce skepticism and outright opposition from dozens of students.

Student response has been significant enough to push the decision on the matter until October, if not beyond.

Much of the conversation has been framed by two issues that have enveloped the nation in recent years—high-profile police shootings of unarmed Black Americans, and gun control debates spurred by mass shootings—and specific tensions that students of color feel exist between themselves and DPS.

The consideration, which stems from a commission review of a 2011 report on DPS and comes despite no significant increase in on-campus crime, sparked student outcry at two information sessions—one for the public on Tuesday and one for student leaders on April 13—focused mostly on the firearms question.

Students Skeptical at Sessions

Both sessions saw many students in attendance loudly reject the potential of armed DPS officers—who would have as much training as New York requires of its police—with students at last Wednesday’s invite-only meeting raising questions of racial discrimination in police shootings and those at Tuesday’s bringing up comparisons to Orwellian dystopias.

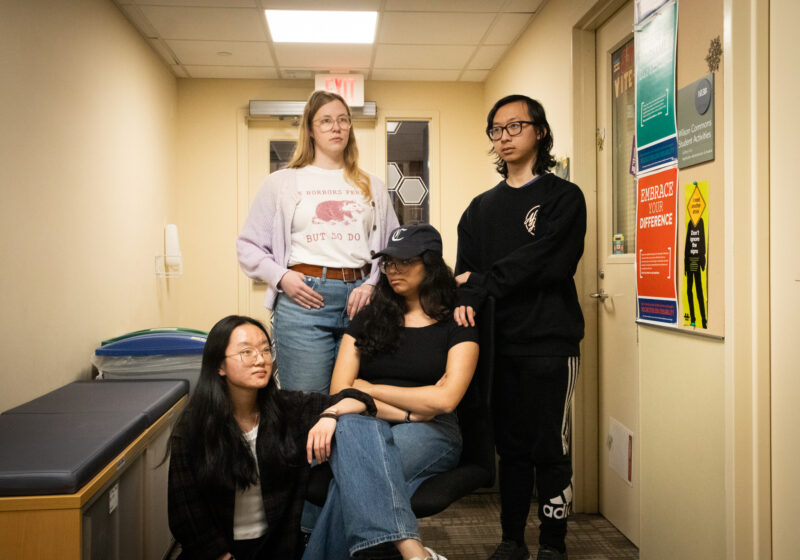

“Given the issues that Public Safety seems to have when it comes to policing the minority students on campus—because they tend to confuse us with the Rochester community and feel like we don’t belong here, we don’t go here—these eight hours of diversity training obviously, I feel like, aren’t enough,” began one student last Wednesday, “How do you stop Public Safety from killing Black students?”

Director of Public Safety Mark Fischer, who is a non-voting advisor to the commission and co-hosted both sessions, replied by pointing to DPS’ record: Its officers had only used pepper gel five times in the past two-and-a-half years they’ve been equipped with it, and had only used a baton “maybe” once during that period—each time never on students.

“We really resolve 99.9 percent of the things that we are engaged in at a very low-level use of force,” he said.

The next student to speak, another Black female, said that most police officers are not “trained well to deal with brown and Black people,” and that she assumes DPS won’t be the exception.

“If we’re looking at the statistics that you guys rely so heavily on,” she continued, “something is going to happen, where an innocent Black or brown body is going to be assassinated by one of your officers.”

She then claimed that there have been instances of campus cops shooting students at other schools, at which point Fischer responded that he was unfamiliar with any incident like that.

Some in attendance scoffed noticeably when Fischer did not address a lengthy follow-up statement from the student, instead asking the audience if there were any other questions. The student promptly left.

Fischer said in a later interview that he had not detected a question in the student’s response, and that he meant no offense by not acknowledging the follow-up.

The Campus Times attempted to contact leaders of campus groups that have spoken out recently against racial discrimination in policing, but none replied.

The scrutiny leveled upon Fischer and other administrators that night did not let up on Tuesday, in a meeting that went almost two hours over its planned duration.

Sophomore Joey Stephens, an incoming Students’ Association (SA) senator who spoke several times during that night’s question-and-answer period, complained of students lacking a voice in the matter.

“All I see is what I can do to affect finances,” he said to Commission Chair Holly Crawford, who is the University CFO and the Senior Vice President of Administration & Finance. “We’re not satisfied with the voice you’re giving us.”

Stephens, a member of the Meridian Society, threatened to protest the possible decision during campus tours—his self-described “nuclear option”—and said repeatedly that he didn’t know what else he could do to get Crawford and other administration to listen.

“I have been listening,” Crawford responded.

Peace Officers Only

The report the commission is reviewing recommended creating a mix of sworn “peace officers”—standard DPS officers who train an additional 670 hours, as much as New York requires for police certification, minus firearm training—and non-sworn officers—state-licensed security guards who cannot arrest—in DPS, as well as changing its name from University Security.

Only sworn officers can be armed, and not without a minimum additional 96 hours of firearms training—a threshold, Fischer said in an interview, that DPS would “obviously” surpass.

UR has 77 non-sworn officers and 66 sworn officers, including sworn command staff. According to Fischer, all 66 sworn officers could, in theory, be armed, but he noted that any option was on the table, including arming only a fraction of that force.

UR is the only member of the Association of American Universities (AAU)—an organization of 62 prominent research universities in the U.S. and Canada, public and private—with a sworn department that is unarmed, according to Dana Perrin, DPS Public Information Officer and Assistant Director of Public Safety for the River Campus. Fifty-nine of the 60 U.S. schools in the organization have sworn officers—only Columbia University does not.

Within New York state, the City University of New York system, like UR, employs sworn officers who do not carry firearms. Perrin noted that four-year colleges within the State University of New York (SUNY) system do arm their sworn departments.

And locally, Perrin said, Monroe Community College and SUNY Brockport “are both sworn and armed” and RIT is “beginning an arming program.” St. John Fischer and Nazareth, on the other hand, have non-sworn and unarmed departments.

The recommendations will be handed to University President Joel Seligman, who can reject them or pass them further, to UR’s Board of Trustees.

Seligman had originally been slated to receive the recommendations in May. But in response to a student concern, Crawford decided during Tuesday’s discussion that the commission should only finalize them during the normal academic year—not at its close or during the summer.

According to a release from outgoing SA President and Vice President Grant Dever and Melissa Holloway and their successors Vito Martino and Lance Floto, Crawford is open to holding more student forums on the question. The executive pairs also expressed interest in organizing an SA-hosted forum.

In an interview after Tuesday’s forum, Crawford said that Martino had volunteered to work with the commission over the summer.

School Shootings Fuel Some Views

Anna Parker, a senior, is a survivor of a high school shooting. She does not think DPS should arm officers—not on the River Campus, at least.

“I feel that arming [DPS] on the River Campus would decrease the trust the student body holds for our [DPS] Officers,” she said in an email. “I do not think the escalated race-based tension, nor the fear on the part of students of color on our campus, is worth the arming of all sworn officers on the River Campus.”

At the April 13 meeting, Parker engaged with Fischer in a series of questions and responses regarding her perceived use of mass-shooting statistics as generalizations during Fischer’s slideshow presentation.

“Our officer in the place where it happened would not have saved a single life,” she said of the shooting she survived, asking afterward, “How do you weigh that increase in the gap of mistrust and a sense of authority and policing with the narrower chances of solving a mass shooting event?”

Fischer, in response, emphasized that he was not intending to use mass shootings as the sole impetus for arming officers.

Parker said in her email that she left that meeting upset and disappointed. But she came away from Tuesday’s meeting with an appreciation for its shift in tone, which she said focused more on staff safety.

And, while she disagrees with using guns to combat gun violence in principle, she is “not one to negate the legitimate concerns of the members of the Emergency Department of Strong Memorial Hospital, or the staff of the Memorial Art Gallery.”

“I think that the needs of each area of the University should be considered independently and dealt with as separate entities, with large amounts of input from all involved parties.”

Parker added that she met with Fischer and Deputy Director of Public Safety Gerald Pickering Tuesday afternoon, and that she gained a better understanding of DPS’ perspective after 10 minutes of conversation than she did from either formal meeting.

“The PowerPoint used in both presentations, although updated for the second, was still cumbersome and unfocused,” she said.

Junior Grant Gliniecki of Newtown, CT, where 20 children and six adults were killed in a school shooting in 2012, reacted similarly to the two presentations.

“Rapid intervention absolutely matters, but despite how common they are in the U.S., school shootings are rare compared to death resulting from inappropriate escalation of force by security and safety workers,” he said in an email.

Gliniecki, who said he has secondary post-traumatic stress disorder because of the Newtown massacre and that he knew some of the victims, added that “it’s disingenuous and frankly insulting to claim that arming Public Safety officers is predominantly motivated with the goal of ending a mass shooting.”

He said in a later email that he thinks the reasoning the commission presentations used regarding school shootings unfairly lumps together opposition to arming officers with opposition to a measure that could save lives.

“No one wants to argue against something that could, in theory, stop an active shooter,” he said. “This sets up anyone who feels that the solution to guns is not more guns to have to first argue why their argument isn’t permitting or allowing the hypothetical killing of their peers, rather than other problems with lethal arms that are much more relevant and likely to arise.”

He continued, “Using the very real trauma from survivors and collective memory of what is largely the result of failed gun control to suppress arguments against gun access and usage feels like a slap in the face.”

Another student opposed to arming DPS officers, junior Nico Tavella, believes a better use of resources might be investing in the Rochester community, in which crime has increased lately.

“I suggested, as a public health major, the real issue at hand is violence in the Rochester community endangering students on this campus, and the most effective solution would in fact be investing in the local community and mitigating the vast levels of income inequality and violence currently in the inner city,” he said in an interview. “Instead of spending time and money arming our campus security, effectively putting another barrier between us and the Rochester community, we should be investing in healing a very damaged and divided area of people.”

He added that, “To enter the city of Rochester and ignore the issues present in local areas is Gentrification 101, and it is a root of the divide between people that we see today. This divide will be widened, not sealed, with guns.”

Some Students Support

There are some students, though, who are speaking up in support of arming DPS officers and of the University officials working with the commission.

Dominick Schumacher, a senior and an All-Campus Judicial Council associate justice, said in an interview that he believes UR would be safer with armed officers than without, despite students’ legitimate concerns.

“Aside from the benefits to the safety of the officers themselves,” he said, “firearms in the hands of capable and skilled officers have the potential to save lives in any situation where someone threatens campus safety with a weapon—whether that be a knife, gun, or something else.”

Schumacher thinks the campus community would benefit from having an armed officer able to respond almost immediately to a potential crisis, whereas city police would take crucial minutes just to arrive.

“Earlier this year,” he said, “I called DPS to address a male (I believe he was a student) walking on campus with a paintball gun. While I knew it was just a paintball gun, I was concerned that others may not recognize that and some issues may arise from it. Public Safety responded in under a minute, and that situation worked out just fine, but it made me wonder what the response would be like if it were a real gun and he had bad intentions.”

He praised DPS officers as highly trained professionals, as opposed to “the overzealous mall cops that some students purport them to be,” citing his positive interactions with them as both a Residential Advisor and a Community Advisor and adding that he believes the University has been thorough and responsible in its research about whether to arm DPS.

Sophomore Niru Murali, outgoing SA Executive Director for Student Life, echoed similar defenses of the University officials involved.

She, too, thinks DPS officers should be armed on campus, “with the promise that they would go through extensive training [and] seminars on implicit racial biases [and] hold several open forums for students each semester to build a trusting relationship.”

“I want to reiterate that we’re students, and we cannot completely know what our officers go through on a day-to-day basis,” she said in an email interview. “Does our voice matter? Absolutely, and that’s why we have the chance to get involved with these forums. But at the end of the day, we can’t put ourselves in their shoes.”

She said she agrees completely with stationing armed officers at the UR Medical Center—which she called a high-risk area—and emphasized that, through her role as Executive Director, she has been involved in all the student meetings on this issue and seen that the officials involved “have been nothing but receptive to student feedback.”

A Call to Arm

Fischer cited in both presentations several benefits of arming Public Safety officers, including more efficient responses to campus incidents, a greater sense of campus security, and a stronger deterrent effect on campus and community crime.

The greatest gains, however, appear to be in response time.

According to Fischer, the average school shooter shoots one person every 15 seconds. He said that DPS needs to think about response times accordingly—in 15-second increments.

Shorter response times are achievable, he claimed, because Public Safety officers know the community and the geography of campus better than outside forces.

The Rochester Police Department, the nearest armed force, has taken 13 minutes to respond during past active shooter drills—a significant increase from DPS’ one-minute response time. At one person every 15 seconds, the hypothetical death toll rose to 52.

And, the presenters reiterated, that’s just for the River Campus.

Both Crawford and Fischer highlighted the feelings of insecurity at the UR Medical Center, where, on a typical day, a majority of DPS officers are already stationed, and where many wounded criminals are brought for treatment.

“We’re hearing very clearly from the Medical Center: ‘We need to have this, we should have done this years ago, we are unsafe,’” Crawford said at the first presentation.

Fischer, in a later interview, described the Medical Center as labyrinthine and said that, in past drills, external officers have taken a “trailer”—a tagalong DPS officer—to navigate the facility.

When asked if his officers have ever felt like they needed a gun, Fischer said yes, citing a patrol commander “who had a bullet narrowly miss his head” and a lieutenant who had been slashed with a boxcutter, and saying that there have been situations where a gun “could have been useful.”

“But,” he continued, “I don’t want to deceive anyone by saying that this is a common occurrence.”

Fischer said that his officers do regularly deal with armed and known criminals, including gang members—who, he said, “don’t leave their guns in the car.”

Concerns from All Sides

Both Crawford and Fischer have insisted that they are listening to students’ concerns, and add to those concerns of their own.

One presentation slide had a list of these, including “national sensitivity towards racially biased policing,” what arming officers suggests about DPS, and how that will change its officers’ interactions with the UR community.

The final concern on the list: “Officers could be involved in unjustified use of lethal force.”

In response, Fischer touted two things: the additional training that armed officers would need to complete, and a shared sense of community between students and DPS officers.

As part of their current training, all DPS officers complete eight hours of diversity training, two hours of community policing training, eight hours of cultural diversity and sexual harassment training, 16 hours of mental illness awareness training, and 40 hours of training devoted to working with emotionally disturbed people.

These hours come in addition to 110 hours of further training in areas including conflict management, ethics, and situational awareness.

Students at both presentations expressed their distaste for the diversity training figure, saying that it wasn’t enough.

All officers will also undergo training about implicit bias in the near future, which Fischer says will be completed this summer under an outside instructor.

Concerning the connection with the community, the presentation specifically named DPS’ efforts to connect with students through the Department’s “Adopt-a-Hall” program—a program that a small student leader panel, meeting with the commission prior to both info sessions, had praised.

“The highest obligation we have is to protect this community,” Fischer said. “We love this place as much as anyone.”

He said Tuesday that if DPS did become armed, he’d hope their guns wouldn’t be used for decades.

Publisher Angela Lai contributed reporting to this piece.

Correction (4/21/2016): A previous version of this story stated that Parker’s conversation with Fischer and Pickering lasted 10 minutes. Actually, Parker felt as though she had gained a better understanding of the issue after 10 minutes of what became a 90-minute conversation.

Correction (7/27/2016): A previous version of this story stated that UR’s was the only agency in New York state with a sworn department that is unarmed. Actually, UR is the only university in the 62-member AAU with a sworn department that is unarmed. Additional information has been added to give context to that figure.