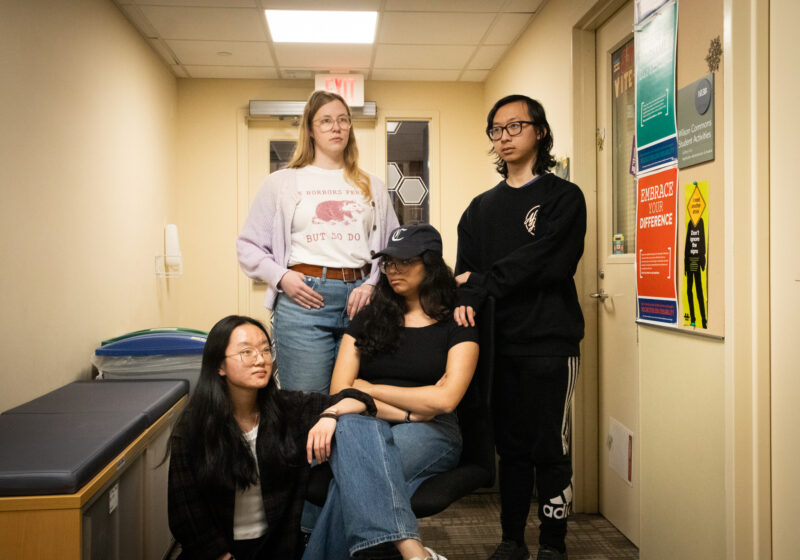

The following article is a transcript of a recording sent to us by Campus Times reporter Avi An-Fletcher. An-Fletcher has not reviewed grammatical or stylistic edits.

You may be wondering why there’s no eggs at Hillside (Correction April 1 2025: There are now eggs at Hillside). You may be wondering why the chickens of campus are quivering in fear, many of whom are masking up for reasons that may not seem obvious. The answer is simple — the pigeon pestilence of 2025, the sparrow sickness, and the mallard malady: bird flu.

Having caused an abundance of peril and an absence of omelets in the American population, we decided to get more insight. Our source? Aptly named biology professor and medical researcher, Sandra Duck.

“So: bird flu …” a Campus Times reporter began, trailing off. Duck seemed confused. “I mean birds usually do that right. They’re like always up in the air. That’s part of their whole thing.” She then went on to explain how bird feathers initially developed for insulation, yet now also help them stay lifted and agile in their flights. “That’s what you’d call an exaptation, a feature that evolved for one purpose but now does something else.”

This response puzzled us. Did Duck think that we were inquiring about birds flying? We tried to clarify, but before we could speak, Duck quickly cut in.

“There’s many birds that don’t fly, however. You’ve probably heard about penguins, kiwis, emus, and the like. But there’s a lot of reasons why [some birds] might not fly, scientists have found. Usually they just don’t want to.”

We asked her if she’s ever seen one of these species fly before, when they wanted to, of course. Duck let out a nervous chuckle and flushed bright red, fidgeting in her chair. “No, I haven’t,” Duck stated. “They would never do that. I thought I just clarified that.”

Realizing we had gotten distracted, our team then asked Duck about the spread of bird flu. She smiled, “I can answer this one. There’s a lot of information about this.” Duck then flipped on her projection screen, circling two oddly large regions of the Northern United States and upper Mexico.

“Birds fly south for the winter. Because it’s warmer.” She then drew two-sided arrows between the two ovals, marking the lower one with a sloppily drawn cartoon sun wearing sunglasses.

“They actually got this idea from butterflies. Birds are very clever animals, you know.” Although untrustworthy, it’s clear Duck is dedicated to her study.

We looked at Dr. Duck, confused. “So, how did bird flu start?”

Duck’s demeanor became clammy, her face scarlet and eyes runny like the yolks of a sunny-side-up. A state of alarm and confusion, I hadn’t expected for what seemed to be such a simple question.

“Did you know there’s birds that can imitate the speech of other animals? Or even humans? It’s been proven they have incredibly strong memories. They have very potent brains,” she said, getting more frantic.

At this point, we knew there was something Duck wasn’t telling us, so we pressed her, again asking how bird flu began.

She paused. Looked around a bit, shuffled in her chair. It had appeared we had ruffled some feathers.

“I don’t know, how did it start? These things are very complicated.” She stared at us, expecting a response. No questions followed. We had nothing to say.

Duck began laughing, chuckling, quacking. Like an egg, she began to crack.

“This whole thing … it’s so bizarre, isn’t it. How a species so fabricated can create panic so real, so tangible. It seems to all be working, doesn’t it?”

She slid over to the back of her office, flipping off the lights and clicking on a projection screen. Images of circuitry and wires in bird bodies spun on the walls, an extended history of the species — no — the machines — for our eyes to see. Birds as surveillance, birds as spies, birds as those freaky reincarnated pets that rich people clone their dogs for. It was under our noses this whole time. There is literally a television character named “Big Bird” spreading propaganda to our nation’s youth. We shivered in the projection light.

Bird flu, she explained, was a hoax. An economic scheme to reduce egg sales and maximize their production while maintaining outside surveillance presence, a sickly happening in factories and in the eyes of “birds” above the city streets. Exactly like what Big Cow did with dairy during WW2 to make people think it strengthened their bones. A hidden undercover conspiracy with unclear motive but clear harm. I was sick. I didn’t know what was real anymore.

“This knowledge can’t leave my office,” Duck crooned. “It’s too valuable, too classified.”

She paused, retrieving a machine gun from her desk. I don’t know how she fit it in there. The first shots fired at the wall, ringing out with a rattle scarily akin to that of a woodpecker. Everything was clicking into place.

“I can’t let you leave this room either.”

All I remember was running, my eyes flashing red and my ears pounding in the storm of noise. A cacophony of bird calls, so it seemed, but I knew Duck was on my tail feathers. That was no bird. It couldn’t be if they weren’t even real.

I don’t know if this recounting will get through to you all. I’m hiding in a bathroom stall with no sign of escape. I’m scared. But this may be our biggest break yet.

The world needs to know about the fowl schemes perpetuated by Dr. Duck. Please share this news. Please. Please. Pl- [the recording ends]

If you or someone you know has heard from An-Fletcher or Duck, please direct correspondence to ct_features@u.rochester.edu