It was Tuesday, May 14 when Rochester’s Gaza solidarity encampment was deconstructed by the Department of Public Safety (DPS).

Final exams had just ended, and as students were ready to graduate, faculty and administration were preparing for a Commencement ceremony free of disruptions. “Everyone wants to take graduation photos in front of Rush Rhees,” said an anonymous member of Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP). “A lot of people had to go home at that point, and we were trying our best to keep as many people [in the encampment] as possible.”

At approximately 7 a.m., public safety officers guarded each entrance to Eastman Quad as others moved to evacuate all members and remove all belongings of the encampment as quickly as possible.

“They told students ‘you have two minutes to pack up your stuff and go before we start taking everything down,’” the SJP member said. DPS proceeded with decampment “30 seconds, like not even a minute later […] People weren’t even awake yet. People didn’t hear what they said, they were sleeping in their tents, and then they fully just started crashing everything.”

“They threw away people’s medication, laptops, phones, wallets, sentimental items,” the member further explained. “Someone I know whose grandma passed away knitted them a sweater [that was thrown away]. Car keys, apartment keys, they tossed it all […] They did not care.”

The encampment had been fully removed within 15 minutes — but its effects on campus advocacy have far outlasted its physical presence. SJP had first touted the idea after witnessing colleges around the country erect encampments as a form of community-organized resistance against the war in Gaza. They began their efforts on April 24.

“It was one, as a form of protest, a visible form of occupation of a space to try to advocate for our demands, which for our school, was academic divestment,” stated the member. One of the primary goals of SJP was for the University to sever academic ties to Israeli institutions as well as a call for a ceasefire in the region. “The whole lead up for the encampment was us receiving backlash from the University, not being understood [and] not being heard or listened to […] the idea was to reclaim a space on campus where our voices were heard and there were people getting together to learn and grow.”

Many of the 15 initial members had carried over from the efforts of UR’s Students for a Democratic Society, who previously held their own encampment to protest student housing conditions. Their efforts sparked a steadfast interest in pro-Palestinian advocacy. “It felt like from there, every night, more and more people came,” the SJP member said. “We made sure people had blankets, food, [and] eventually we got to the point where community members were donating almost every single meal.”

The following weeks saw two sit-ins at Wallis Hall, with the first ending after a preliminary agreement for SJP to present a roadmap towards academic divestment to the Faculty Senate. That agreement, however, fell through after claims that the Senate had unanimously voted against any plans of the sort — a level of miscommunication that ultimately defined the relationship between the administration and the encampment.

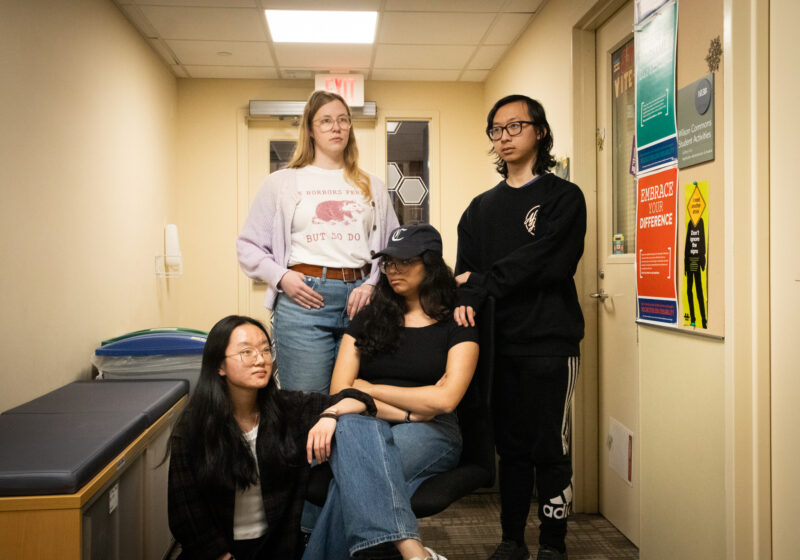

With involved students facing academic suspensions and property bans, the mistrust both parties had in each other ultimately plagued efforts to reach any level of mutual agreement — a relationship that may carry over to this fall semester, where President Sarah Manglesdorf and Vice President for University Student Life John Blackshear emphasized their commitment to an updated protest policy in recent student addresses.

First coming to fruition in the winter of 2023, the policy prohibits outdoor camping of any sort, and limits demonstrations to those approved and in line with restrictions appropriate to the University. These include establishing a Responsible Organizer as a main point of contact between administrators and advocacy groups, as well as limitations on time, place, and manner as deemed reasonable.

“I have deep concerns about the new policies, particularly because in their wide reach, they seem to be applicable to almost any event held on campus at the university’s discretion,” Miller Gentry-Sharp, External Chair of SDS, said. “The restrictions on volume, signage, and materials are deeply concerning and it is unclear to me how the University will go about enforcing these rules.”

“The relationship we’ve had with the University has varied widely depending on the demonstration. During our abortion access campaign, our interactions with admin were pleasant. We had no issue reserving the space we needed, and the administration eventually approved the UHS vending machine that URSHAC helped push through. When we did our housing encampment, we were met with a colder response,” Elena Perez, Organizing Chair, stated. “From our experiences, it appears that University leadership likes to make themselves look open to conversation at all times, but then selectively chooses when to engage and when to withdraw.”

“I do believe that concerns exist,” Elijah Bader-Gregory, President of the Students’ Association, stated. “I think the University is concerned about the [safety and feasibility] of protests […] that being said, having concerns about protests and implementing restrictions on protests are two different things. If there were no protests there would never be any problems at protests, just like if we stopped flying planes they’d stop crashing. But just like planes must continue to fly, our community must continue to support the right to protest and continue to develop inclusive dialogue and decisions on how it can be done best, safely, and effectively, that minimizes restriction.”

Prominent cultural and awareness groups emphasize the desire for healthy communication that promotes the nature of protest rather than its potential effects.

“This policy seems mostly as a strategy by administration to prevent students from gathering,” ADITI stated. With regards to the University’s requirements for designated protest areas, the policy is “so ambiguous as to what it really means, and thus different treatments could be applied from different groups wanting to hold a protest. This will only lead to more strife and more animosity between students and the administration.”

“We believe that students should have the right to protest, and wish that the University would have more conversations with students and leadership of the organizations to create guidelines to ensure safety but not limit their ability to protest,” College Democrats stated. “With respect to our University’s values, [they] must be open and receptive to criticisms that restrictive policies, like this one, are contradictory to our vision of fostering an environment of conversations held in good faith.”

In the aftermath of the encampment and the restrictions that lie ahead, the cause remains the same for SJP, even if their strategy doesn’t. “I think we’ve just learned a lot this past year about what risks we are willing to take that will actually get us somewhere and what risks are just risking students for no reason, and we, as much as possible, have good intentions and want to work with the University. It’s not us versus them,” said the encampment member. “That’s not what the point is.”

“There has never been this many people who know about the Palestinian struggle. There’s never been this many people in the U.S. who kind of understand what’s going on or at least are aware of it,” the member further explained. “With collective action and with years of education and building on this, change will happen.”