In the age of screens, swipes, and saves, our generation has grown used to being bombarded with a slew of visual content and information. On any social media platform, you can scroll through videos of food recipes, fashion tips, news coverage of bombings, movie scenes, scripted storytimes, and a mother filming under a cracked roof in hopes of collecting donations to save her family — all in under two minutes.

I’m not here to tell everyone what we already know; it is undeniable that consuming media in such a way has permanently altered our cognitive abilities, sensitivities, and attention spans. Among the dizzying clutter of content, however, there has arisen the opportunity for a teenager from the suburbs of Virginia to not just discover the plights of a refugee from Syria, but also discover countless outlets and platforms to help the refugee from Syria — and to call for others to help out as well.

What’s come about from the widespread connectivity of the online world and its ability to reach millions within minutes, however, is a form of activism that centers around reshares and reposts. We start to see a snowball effect, where one friend will post on social media and broadcast it to hundreds of followers, and any one of these followers can view the post and reason that — even if they have limited knowledge about the issue — it is worth acknowledging and learning about because their friend cares about it. In a matter of weeks, world issues and crises that gain enough exposure on social media have the power to go mainstream. And, within many social spheres, this manner of amplification through harnessing the power of social media is seen as the right and virtuous thing to do. Here, however, we also tend to run into the tricky term called “performative activism”.

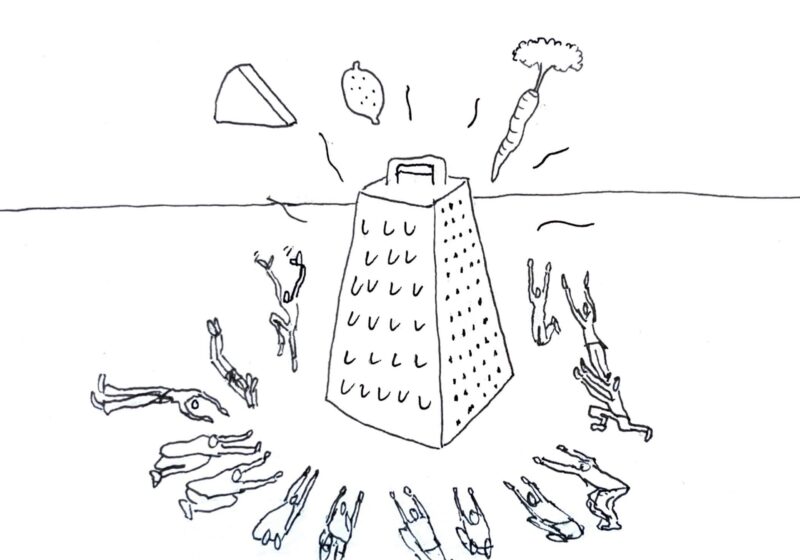

What is the first thing that comes to mind when you think of performative activism? Is it a pastel-colored infographic telling you about the new bill that was passed and how it will be detrimental to the population? A social media post that calls you insensitive and privileged for swiping away? Or, perhaps,an Instagram story of someone who you know has never previously advocated for an issue until it gained more popularity? These examples are widespread and common, and they have seen a parallel increase in backlash that only continues to grow. Certainly, when the tendency for questionably fact-checked information to spread rapidly is coupled with the obligation, social pressure, and virtue signaling felt by many in our generation, it can be a recipe for low-effort attempts at activism that appear insincere and diluted.

Having the death toll and destruction of a catastrophic bombing be compressed into a dusty pink graph with bubbly font surely causes many of us to feel uneasy and frustrated; it is as if the horror and magnitude of such an event is being wrapped up into a pretty and palatable bow for people to share and advocate around in the most aesthetically pleasing way possible. What’s more, by lowering our definition of advocacy to something as easy as a repost, less people may be inclined to go out to the streets to protest, boycott, or push back against administrations. But are the critics of these “easy reposts” contributing more impactful forms of activism themselves, or has hating infographics and other forms of “performative action” become an easy way to signal superiority and discredit the significance of raising awareness through social media in particular?

While ill-intended activism derived from wanting to look like you are doing the “right thing” by blindly reposting information that hasn’t been fact-checked is deserving of criticism, the kind of harsh backlash that these actions face seems to undeservedly surpass even the criticism directed at people that remain silent. It is almost as if criticizing performative activism has become the easiest way for people to discredit movements, or for people who do not wish to do any activism themselves to still appear virtuous and on the “right side” within their communities.

Ultimately, there is no clear-cut definition of what performative activism looks like, and it is not possible to definitively ascertain someone’s motivations behind their attempts to raise awareness about crises and injustice. While we should absolutely be criticizing the spread of potentially misleading information and half-assed attempts at advocacy, it is important to consider that there is power in numbers. In the age of screens and connectivity, it can be transformative for messages to spread through social media and potentially reach millions of people — especially when many of these injustices are faced by people who lack the same resources to spread their words without the help of crowds and global visibility. We should also be questioning the motivation behind hating on social media reposts, and ask ourselves: If you think that person’s Instagram story isn’t helping the cause, then what are you replacing it with?