One of the most terrifying things I hear on a daily basis is that everyone knows me.

Sounds silly, right? After all, in high school, I remember wishing to be popular — in the cartoonishly exaggerated way that movie characters were popular, sure, but nevertheless. It’s easy to wish for things you can barely fathom. It turns out that popularity isn’t exactly what you think.

In high school I considered myself someone who, while not well-known, was well-liked in my circle of friends. My friends, however? To me, they all filled these specific archetypes — the class clown that somehow also had the highest grades, the straight theater boy that everyone had a crush on, the musical prodigy with a quick wit — that everyone loved. I, at least in my own head, remained incredibly average and middle-of-the-pack. It was nice to let myself be part of the masses while also having my small ways to shine: the long-awaited solo in choir, the occasional well-spoken presentation in class.

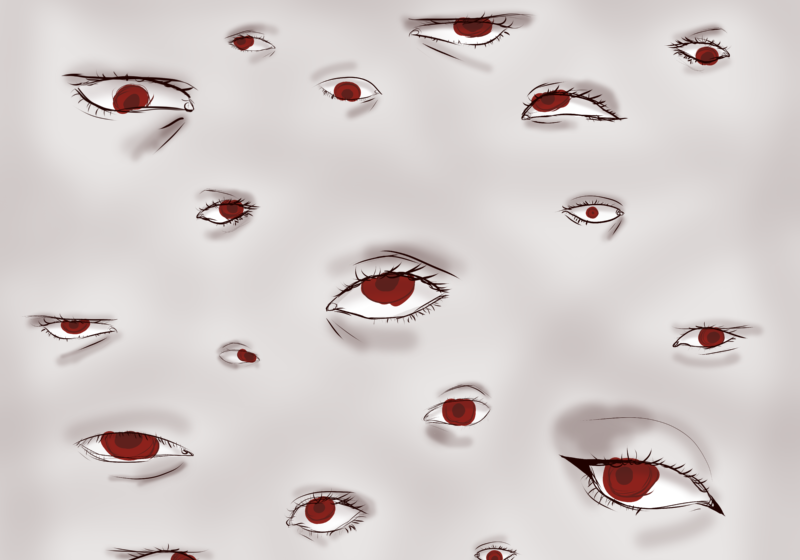

It’s not that I consider myself actively popular now, and I don’t even think I would want to be popular per se. However, the drastic shift between being a background character to being perceived frequently by more people than expected stressed me out. I wave to people in the hallways, I talk to friends about names and faces they can’t place, and most of all, I get talked about when I’m not around. I’m sure that happened before, but it’s never been this apparent to me.

If I embodied any archetype prior to college, it would be that of the side character. I often felt uneasy talking about myself and my problems, so I stayed one-dimensional by choice and let others do the complaining. After all, if there wasn’t anything special about me, I could at least be perfectly average and unproblematic, and people would still gravitate towards me. Being a point of stability for others, especially amongst hormonally imbalanced, intensely insecure teenagers, is an underrated character trait. As a result, I got incredibly used to forgetting about my own issues in lieu of listening to someone else’s. I didn’t expect that when coming to college, I’d suddenly find myself amidst a crowd of people that not only wanted to know me, but wanted to know things about me — even the not-so-savory things.

When I got together with my current partner at the beginning of this semester, it came off the heels of an amicable yet painful breakup, a full-fledged identity crisis, and an anxiety-inducing, socially stressful job. I didn’t want to talk to my friends at college about any of it because I didn’t want to be viewed as unable to be a support to others, and I was especially anxious about being brought up in speculation about what had happened over the summer. I thought I could blend back into the crowd and disappear. Ha, nope. Turns out that once people start caring about you, they also care about what happens to you — both the good and the bad. It felt suffocating instead of reassuring, and I had to relearn how to talk to people without fearing that they’d ask me a question about myself. I could be a topic of conversation simply because people wanted to know about my life, rather than because anything I was doing — even if it felt uncomfortable to me — was a hot-button issue.

Inevitably, I learned that being perceived constantly doesn’t mean that you’re under scrutiny the entire time. Life isn’t like the movies, and just because people speak about you doesn’t mean that they’re gossiping. I’m not the main character of anyone else’s life, thankfully — but that doesn’t mean I have to relegate myself to being near-obsolete in people’s minds, especially my friends’.