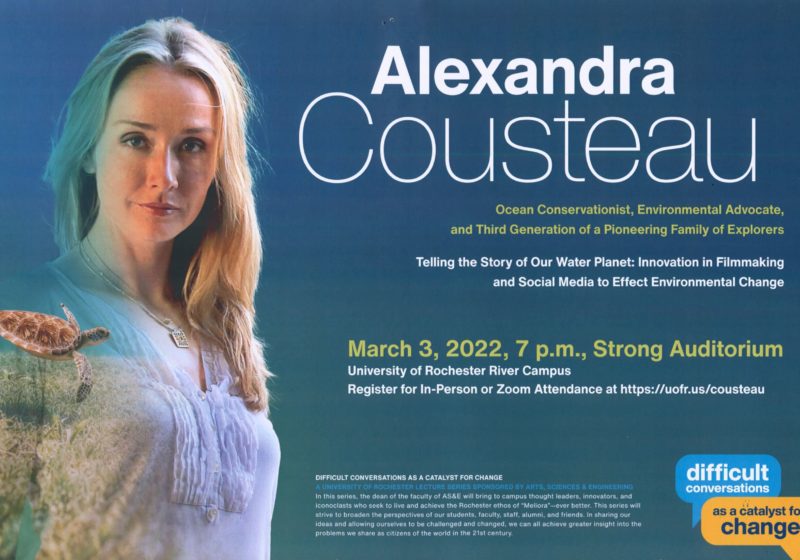

Before everyone left for spring break, there was a minor yet notable speaker by the name of Alexandra Cousteau who came to campus. I’m sure you’ve seen the promotional poster all around campus with the heading “Ocean Conservationist and Environmental Advocate” above a picture of a photogenic woman. But who was this woman? Who cares?

Two words: Jacques Cousteau.

Still nothing?

Jacques Cousteau is an adventurer (of sorts) who is credited with the invention of open-circuit scuba gear. This Alexandra happens to be the granddaughter of Jacques Cousteau, but the Cousteau family has not floated on without scandal since Cousteau Senior’s death. Google “Alexandra Cousteau and Jeffery Epstein” and see for yourself. Read pg. 68 of Virginia Roberts’ Billionaire’s Playboy Club.

Right as everyone was leaving campus for spring break, most without the desire to look back, I found myself in a roundtable discussion with Alexandra before her official speaking event at the University. This gave me the opportunity to have an audience with a few other students, all discussing a research article called “Rebuilding Marine Life,” which would serve as the basis of her talk later that night.

Upon researching current trends of ocean conservation and environmentalism in preparation for my audience with Cousteau, I couldn’t help but notice that when you look up “Alexandra Cousteau,” her own website comes up. Upon clicking, you’re greeted by a blond-haired, blue-eyed woman smiling, sitting in front of what looks like a wetland, with the sun shining over her right shoulder. The heading says “OCEAN ADVOCATE” in bright, white lettering.

The photos are staged in an almost uncanny way, with the focus always being on her. Some photos make you wonder whether she is modeling clothes or advocating for environmentalism. Cousteau could be swimming in a river wearing one of her grandfather’s patented snorkels, yet she’s still able to look directly at the camera in a stylish way.

Huh.

The “About” section could itself provide the dictionary definition of propaganda: “She could swim before she could walk and was one of the few who learned to dive with SCUBA from Captain Cousteau himself at the tender age of 7. Her childhood friends were the sea creatures that inhabit the rocky shorelines of the south of France. The ocean has been her guide ever since.”

The website focuses nearly entirely on her, with little to no information about any actual conservation efforts. It looks more like a marketing campaign for her connections and brand than for actual contributions to environmentalism.

This got me thinking: what does Cousteau do? So, I turned to Google once again, and this time researched her grandfather, to whom she partly owes her public prominence. While Jacques Cousteau made considerable contributions to the study of oceanography in the twentieth century, he had his problems as well. Under his leadership at the Monaco Oceanographic Museum, study of an invasive algae — Caulerpa taxifolia — led to the algae infecting the Mediterranean Sea, destroying marine ecosystems.

While Jacques’ contribution has been felt, the good and the bad, it still made me wonder what contributions independent of her grandfather Cousteau had made. Up to this point, I was getting the impression she was riding off the coattails of her late grandfather, which does hold a grain of truth.

Diving deeper, I attempted to corroborate Cousteau’s clearly biased website with her Wikipedia page. One source that stood out listed her as part of the advisory development board for an experimental “green” city in the northern coastal corner of Saudi Arabia named Neom. Neom is advertised on its official website as “the future as a new home” and “a virgin area that has a lot of beauty.” The problem, however, is that the land where this city is to be built belongs to the Huwaitat Tribe. Saudi Arabia has an authoritarian government that does not allow for dissent against its actions; dissent is traditionally crushed through extensive jailing and extrajudicial killings. Since 2020, the government of Saudi Arabia has been forcibly removing the Huwaitat people to make room for a city that is advertised mainly for foreigners and not the natives.

At the time of my audience with Cousteau, I asked her about these human rights violations. Her response to my questions, after a long pause, was to shift blame to anyone but her.

“Let me say, I’ve been on the [Neom] Development Advisory Board, but I’m not in charge of anything, okay […] that project is in a unique position to scale technologies that can help the rest of the world and accomplish […] developments that we desperately need around the world but no one else has developed or scaled.”

She further insisted that the Saudi government’s “environmental commitments are extraordinary.” Most tellingly, on the subject of the displacement of the Huwaitat Tribe, she said, “There was one person who died and it was because, [despite] all the efforts for compensating [the Huwaitat Tribe] and moving them […] that person chose to take guns and attack the authorities, and was killed in the process. And that is very unfortunate, but it wasn’t a result of the policies.”

Since many others also asked questions, I was not able to further my questioning with her. But analyzing her argument and perception of the events that transpired in early 2020 in Saudi Arabia called to attention Cousteau’s unwillingness to protect displaced human beings with the same vigor she puts into protecting displaced animals.

In her answer, Cousteau spoke of eminent domain — the right of the government to appropriate private property for their own purposes, with compensation to those affected. She spoke of eminent domain as a simple fact of the world, something that happens everywhere — but so is pollution. She recognizes that pollution can be both a universal truth and something to be stopped, so why does she turn a blind eye to the displacement of people?

Contrary to what one might assume, Cousteau has no former training in oceanography or any other academic branch of environmentalism. Her formal education consists of a bachelor’s degree in Political Science and Government from Georgetown University. Thus, she cannot speak to the scientific approach of maintaining the world’s marine ecosystem. While she claims that she is merely an advisor, not a decision-maker, how is that any different from her previous forays into ineffectually discussing environmentalism with world leaders?

Cousteau claims the Saudi government gave reasonable warning and compensation to the Huwaitat Tribe. Tribe members say otherwise. While there may have been warning, tribe members have reported a lack of compensation or alternative housing after the forced removal. To boot, this new “entirely green” city reportedly has plans for robotic maids, flying cars and glow-in-the-dark beaches. How realistic is this project that Saudi Arabia is willing to displace its people to accomplish?

It is obvious to me that Cousteau has interests, financial or otherwise, in Neom, but the reality of her pipe dream remains clear to everyone but her: Opposition to the arbitrary decisions of a dictatorial authority spells death for all those without the luxury of being the granddaughter of a famous inventor. One of the Huwaitat people died because he did not want his land taken away from him. Despite the Saudi government’s claims, this man — like many of his tribe — was left without any avenue for resettlement or compensation for the theft of his home. How can we invite speakers to this University that do not use their prominence on the global stage for the benefit of humankind, or refuse to acknowledge humanitarian issues? It saddens me that in a time when humanitarian issues are receiving greater attention than ever before, there are people that knowingly support the selfish and inhumane decisions of authoritarian governments. Moreover, we willingly invite them onto our campus.

UR, you need to do better.

Alexandra Cousteau, you need to do better.