My name is Sunahra. Sun-ah-ra. I love it. My name is intrinsically linked to my identity — to my culture, heritage, and family. My name was a gift from my grandmother. It was a blessing from Bangladesh, my motherland. My name informs who I am.

My name is important to me, and so I hate it when my name becomes something people think they can change. Time and time again, when I meet new people, I immediately have to be confrontational and authoritative to ensure that they call me by my actual name and not some Americanized monstrosity. I can never understand how strangers possess the audacity to say that because my name was too “hard” to say, they wanted to call me something else. I hate that my name has to become a thing the first time I meet someone.

It is deeply ignorant to ask someone to go by another name just because you think it’s difficult to pronounce. It’s ignorant to thrust random cutesy nicknames at a stranger because you do not know how much value they hold in their name.

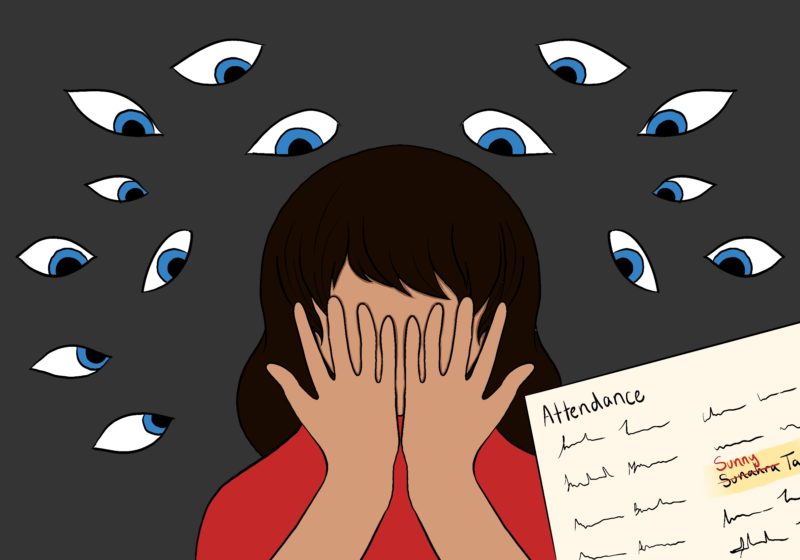

Growing up, I remember dreading the first days of school when new teachers didn’t know how to say my name. I dreaded roll call — they’d butcher my name and then ask, “Do you go by anything else?” I dreaded being the only child who had to say anything more than “here.” I dreaded my name becoming a conversation, a thing, just so my teacher could have some time to get over their embarrassment. “Oh! So pretty! What does it mean? Where is it from?”

No matter how many people have asked to call me something else, I have always insisted that I be called Sunahra. But that insistence can become exhausting. I know other ethnic children who just gave up, who didn’t want another conversation about why they don’t want to be called Amy instead of Amita or Mo instead of Mohammed.

I remember in elementary school how a teacher called one of my classmates — Mwafuq — “Zain” just because she didn’t want to say “fuck” in class. I asked him why he let her do that, and he told me that rectifying it “wasn’t worth it”.

I understand that. I find myself getting tired too. I let my favorite art teacher mispronounce my name all three years of middle school. The first time she mispronounced it, I corrected her. When she continued to mispronounce it differently, I didn’t want to embarrass her. So for 6th, 7th, and 8th grade, I was Sun-AY-ra. At Starbucks, I go by Sarah. I let my high school boyfriend misspell my name two years into our relationship.

It is tempting to want to go by a westernized name just so I can adopt a modicum of whiteness, so life can be a little bit easier. But despite all the imaginative ways my name’s been altered, I don’t think I could ever completely let go of my name fully. I really do love my name. My name is a thread that connects me to my family who are thousands of miles away. I can’t stop using it. I won’t stop using it.

Western ignorance forces ethnic children to sever one of the few connections we have left with our cultural identities. We are already thousands of miles away from the countries we immigrated from, and western culture has molded us into something too foreign to ever be able to return and wholly fit in. We will not be stripped of our names as well.

It’s disrespectful to change someone’s name. A name you come up with in a second will not be better than a name that my parents and grandparents ruminated over for months, a name weighted with rich heritage. My name is proof of the love and care my family has for me. I already have a name — I do not want a new one.

If a name looks too hard, please just ask how to say it. Please don’t try to rename me. I will not change my name because it inconveniences you. My name is who I am.