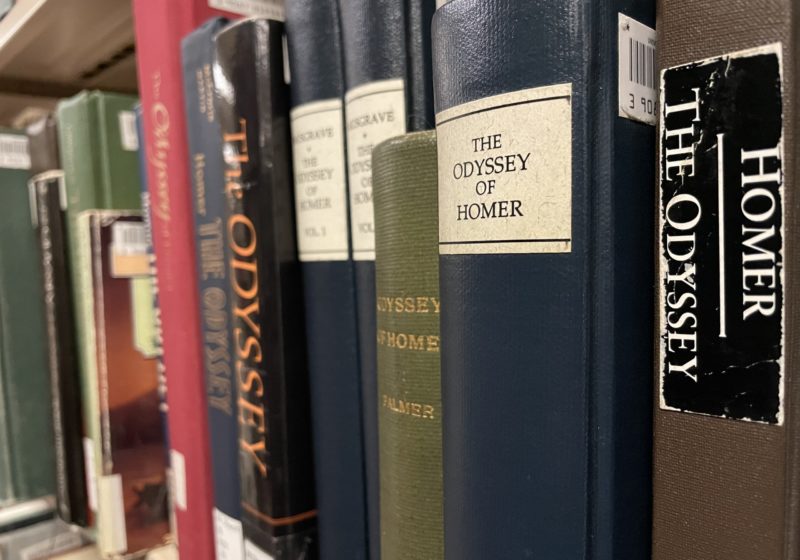

In the Humanities Center’s first major public lecture since the beginning of the pandemic, the University welcomed bestselling author, critic, and classicist Daniel Mendelsohn this past Thursday to speak on his reading of “The Odyssey.” In many ways, Mendelsohn’s visit to the University was focused on expanding our understanding of the many voyages we embark on throughout our lives. Prior to the lecture, which was titled “The Odyssey and its Migrations: Wandering, Homelessness, and Identity,” Mendelsohn offered to meet with a small group of undergraduate students, many of which were either Meliora Scholars or HRIG Scholars. The students had the opportunity to engage in an hour-long discussion with him about his writing process, storytelling, and shifting interpretations of classical texts. They also discussed in detail how his relationship with both his father and “The Odyssey” evolved as a result of the two of them exploring the text together a year before his death — the focus of Mendelsohn’s 2017 book “An Odyssey: A Father, a Son, and an Epic.”

In addition to speaking to students about the ways in which “The Odyssey” can be reframed and read as a story about fathers and sons, Mendelsohn also talked to a larger audience about how the epic can illuminate issues such as migration, national identity, borders, and xenophobia.

Mendelsohn started his lecture by marking the occasion as a symbolic homecoming of sorts, after almost two years of many of us undergoing our own personal odysseys. In experiencing “new and strange ways of being in the world,” “unbearable distances from loved ones,” and “terrible new insight into the meaning of the word pain,” we, too, have become Odysseus, he said.

He then explored how the epic poem addresses issues of migration, refugees, and walls “both real and imaginary.” To support this interpretation, Mendelsohn first delved into the nuances of the word choices in the Ancient Greek text and how they illustrate themes of wandering and pain. He then made a distinction between two contrasting aspects of the protagonist Odysseus’s character: his active role as a violent explorer and conqueror, and his passive role as a refugee and wanderer. He argued that Odysseus is an emblem of a particular brand of masculine heroism; the epic celebrates a “certain kind of political hegemon” by portraying him going on adventures and defeating enemies, resisting the temptations of the seductive Calypso and Circe, and returning home to regain his rightful status as husband, father, master, and king. He is reminiscent of the classic Western explorer: an emissary from an advanced civilization, driven by his belief in his right to intrude on and disrupt unfamiliar societies.

This white imperialism — his Columbus Complex, an Alexander Archetype, call it what you will — irreversibly changes the societies he ransacks for the worse. Perhaps the most well-known of Odysseus’s imperialist adventures is his encounter with the one-eyed Cyclops, who is often thought of as an uncivilized monster, vanquished by Odysseus’s brilliance. However, the Cyclops is in fact a victim of Odysseus and his men’s violence, his home invaded and he himself physically mutilated.

In contrast, Mendelsohn pointed out that the second aspect of Odysseus’s personality is that of a helpless wanderer, needy and abused. He is rendered nameless and invisible: a stateless non-entity, lost at sea and separated from those he loves. It is only when he experiences this suffering — which is uncannily similar to that of many refugees — that he is led home. Mendelsohn discussed the implications that this complicated duality in Odysseus’s characterization might have on how we think about migration and identity. The distance between our experiences and other people’s is the “first boundary we’re faced with,” he said. To extend past that distance by “confronting” the suffering of other people — recognizing our role in their suffering and in its alleviation — is the first step to doing “the work of dissolving other boundaries.” Mendelsohn stressed that we should strive to help turn “all the world’s no ones into someones;” that is, guaranteeing that vulnerable groups such as migrants and refugees are treated with dignity and respect, and ensuring the security of their identities and homes.