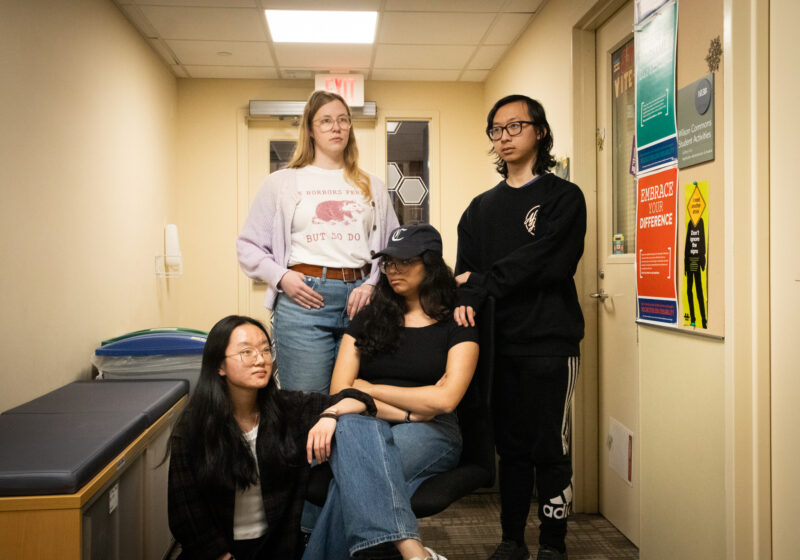

Growing up, I always admired people who could just walk into a room and make friends effortlessly. As someone who recently compared herself to diced fruits in an earnest attempt to socialize, this was not my reality. As a result, those people — extroverts, as I perceived them — were the blueprint of who I aspired to be.

Aside from just wanting to know what it felt like to be at ease around others, I wanted to be an extrovert because I thought that was the way I was supposed to be. I never quite fit in with stereotypes about Americans being loud and charismatic, and since that was my baseline for normality, I viewed myself as different.

Beyond just wanting to blend in, though, I was always stuck on the idea that bigger personalities could accomplish more. I felt like there was this unspoken consensus that effective leadership came from flashier personalities, so I began to conflate outgoingness with success.

Ironically, I started letting go of the idea of that extroversion would help me achieve my goals when my skills as a leader were put to the test.

When I was 16, I volunteered as a counselor at a science camp for a week, where I was responsible for supervising a dozen fifth graders. Due to some pre-existing feuds among my campers that I was ill-prepared to handle, the atmosphere among our group was sheer chaos, and I spent the first half of the week hoping our cabin wouldn’t go down in flames. Although I tried to address conflicts as they arose, it seemed there was always another issue waiting in the wings.

Every night, counselors were supposed to read from a binder of bedtime stories, but as my campers were getting ready for bed on Thursday, things reached a boiling point when one of my campers accused another of ruining camp for her. After I called in a teacher, our cabin was finally silent, but the lurking tension made me realize that my campers’ experience would end on a sour note if I left things unresolved.

Instead of reading from the binder that night, I decided to share a positive memory I had of each of my campers that week — and although we went through some stressful times together, it was easy to remember the special moments we had.

Afterwards, I invited my campers to share their own memories, and watching the vibe in our cabin transform as they highlighted the good moments in the week gave me the feeling that finding my own ways to be a leader could be good enough.

At 19, I’m still learning how to be a better leader, but I’ve also gotten better at growing in my own direction rather than forcing myself into a mold that never really fit.