When a first-year from China took an Uber two weeks ago, he thought the driver seemed nervous.

“The driver asked me where I’m from,” the first-year said. “I said China. He didn’t even stop here, he asked which city. I said, ‘I’m not from Wuhan, don’t worry, I’m from Shanghai, it’s a safe zone.’”

That first-year — who the Campus Times gave anonymity out of concerns for his safety from the Chinese government — is one of several UR Chinese international students who spoke to CT about how Chinese students are affected by the new coronavirus, thousands of miles from the outbreak’s epicenter.

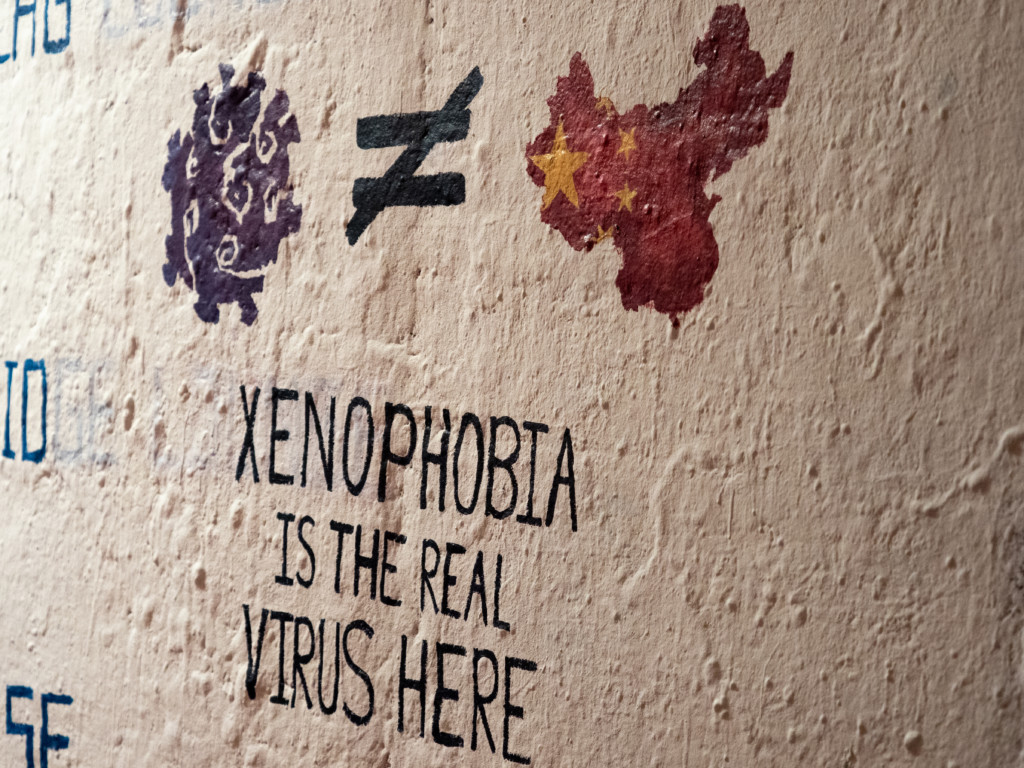

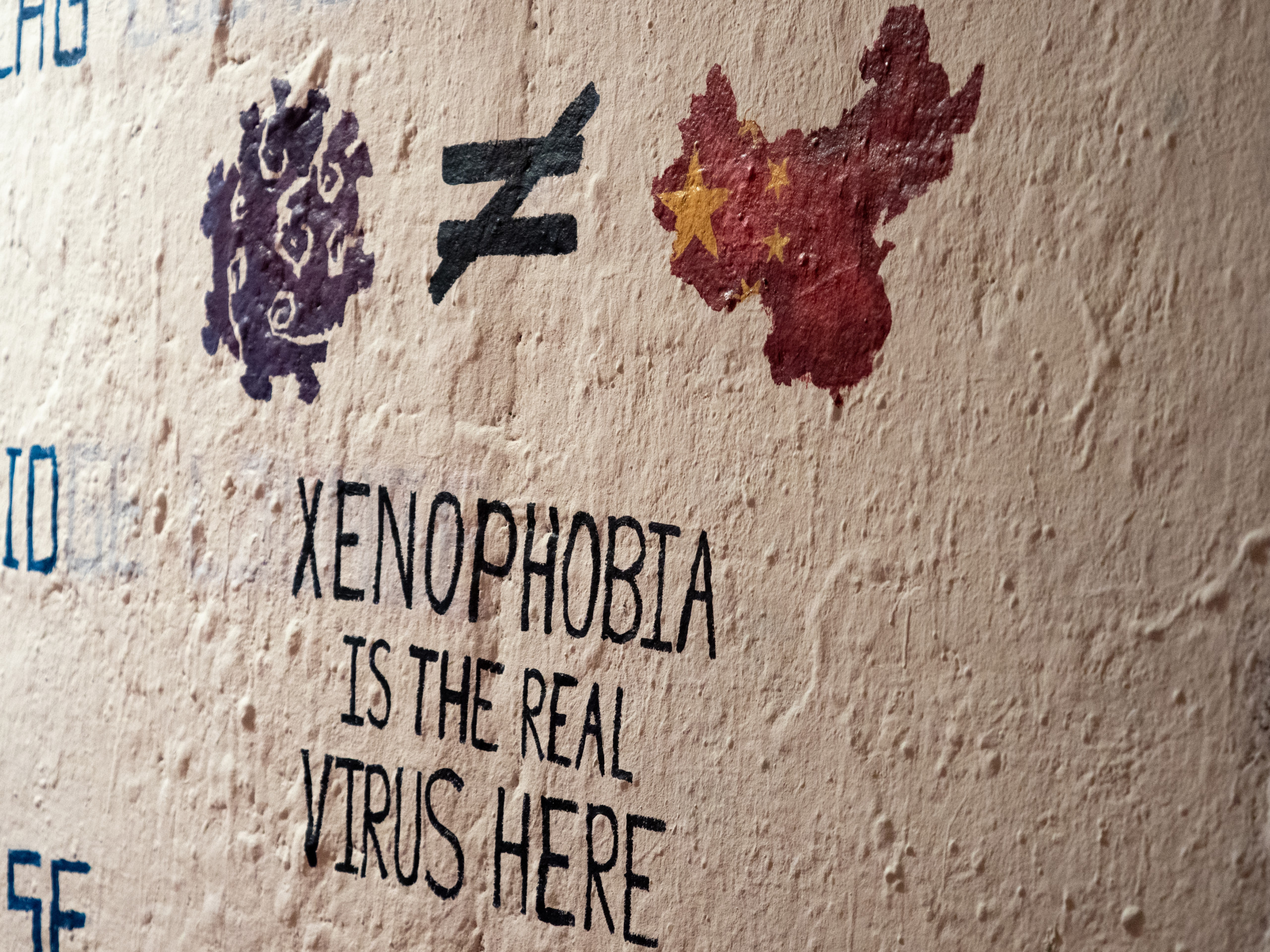

Sampson Hao, a junior and the president of the Chinese Students’ Association (CSA), said that fears regarding Chinese people because of the outbreak are misplaced.

“Because we don’t know the mechanism about the virus, it doesn’t mean that Chinese students should be targeted. It doesn’t mean that Chinese students should turn against each other.”

The first-year from Shanghai agreed.

“There’s very small chances of any patients being infected by the virus in UR,” he said. “Because most of the Chinese students, they came into the U.S. […] seven days before the major outbreaks.”

Last week UHS Director Ralph Manchester said in an email that there is “no indication that novel coronavirus is or has been present on any of [the] University campuses.” Though UR remains a coronavirus-safe environment, the coronavirus’ death toll rises, recently hitting 1,017 in China.

The first-year from Shanghai said concerns for friends and family are still strong for Chinese students.

“I don’t know anybody who is infected, but I know basically every one of my friends, every one of my family members, they are affected by the virus,” he said.

A senior Chinese international student — who requested anonymity to avoid retaliation by China’s government — said that while concerns have swirled among Chinese students about students back from virus-hit areas attending classes, it would be impractical to expect students to quarantine themselves.

Fears of coronavirus at UR were at least in part prompted by a misunderstood email from an optics professor, shared on campus in past weeks.

Yibo Hu, a junior from Wuhan, the outbreak’s epicenter, said he believes the desire for students from Wuhan to be screened for coronavirus is not discriminatory. He stressed, however, that it was “inappropriate” for anyone to share the screenshot of the email, as he said it constituted the disclosure of a student’s personal information.

Some have responded to anxiety with action — CSA, as well as the graduate organization Chinese Students and Scholars Association (CSSA), organized fundraisers responding to the increase demand of medical supplies in Wuhan and the rest of the Hubei province.

At the beginning of CSA’s annual China Nite on Feb. 7, there was a moment of silence for those lost to the coronavirus. CSA has promised to donate 2,000 face masks — plus another one for every audience member that attended — to Wuhan. Hao, the president, said they are still confirming the purchase with the manufacturers and establishing connections with potential recipients.

CSSA announced through their official WeChat account that they will be donating $1,000 to Wuhan Puai Hospital and encouraged students to join them in the online fundraiser that ended on Feb. 9.

While Hu — the student from Wuhan — was cynical about the efforts, saying it was “too late,” the first-year from Shanghai praised the fundraisers.

“I think it’s a good move,” he said, “because I think masks and protection suits, people cannot get access to that in China now.”

Both anonymous students spoke about the effects of the virus on the Chinese government and the discussion sparked among China’s citizens.

“I’ve lived in China for 19 years, so I’ve never seen such a wide discussion about free speech or free press,” the first-year said.

The first eight people to draw attention to the virus, before the Chinese government acknowledged its existence, were arrested for spreading a rumor. “Those eight people didn’t do something wrong,” said the senior, later adding, “They were trying to warn people, and police arrested them.”

A Jan. 1 announcement by Wuhan police on Weibo (a Chinese Twitter-like social media platform) stated that they’d “taken legal measures” against the whistleblowers, who the police described as having “published and shared rumors online” that “caused adverse impacts on society.” The post has since been removed.

Wenliang Li, a doctor and one of the whistleblowers, died of coronavirus on Feb. 7, resulting in public outcry including an article in Shanghai newspaper Xin Min Wan Bao criticizing the Chinese government’s lack of transparency. In a country where the government controls the news media, stories critical of the government are exceedingly rare.

The first-year said that, despite the threat the coronavirus poses, these discussions give him hope.

“This is a big deal,” he said. “Even the state-controlled media itself has challenged the drawbacks of the state. And I think I’ve never seen things like that before.”