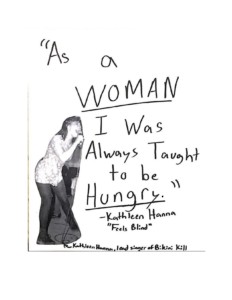

I don’t know how I’m supposed to feel about what I eat.

Sometimes, as a thought experiment, I try to imagine what I would do if I didn’t live in America. If I instead lived somewhere where I didn’t have to worry what other people thought about how I looked.

But I can’t really imagine that place, and since I don’t have any idea what a truer, more independent me would think, I can’t decide what I should do when given the choice between a resounding “fuck the man” and a quiet acceptance of my place.

I am not targeted by body-shaming and misogyny to the extent of some women. I am white and within a socially-accepted weight range, which makes my life much easier than it does for other women.

I’ve still learned to keep a tally of my faults. Recently added to the list once again after a brief departure is my stomach, which sticks out more than it should in proportion to the rest of me. In the past, whenever I’ve felt overwhelmingly aware of this, I would go online and look for workout routines and diet restrictions that I wouldn’t maintain for more than a few days.

As a result of my tours of the “fitspo” side of the internet, I have acquired quite a bit of useless information. For instance, the hourglass figure, defined by a curvaceous yet somehow still slim silhouette (which I have decided must be mine if my appearance is not to disgust everyone around me), is only the natural body shape of around 8 percent of women.

These women’s bodies store most of their fat in the gynoid region — the breasts and buttocks — while avoiding the legs, hips, and stomach. Whether you are born with this body type depends on genetics and random chance, making it unattainable (a word that has come to fill me with dread) for most women.

However, according to the sites I frequent, this figure can be yours! With a combination of rigorous exercise, balanced eating, and patience.

None of these activities interest me, and as I sleepily scroll through yet another article with the hope that it will reaffirm my self-pity and finally allow me to call off my quest for a better body, I find it unfair that I’m not one of the chosen 8 percent of women whose bodies fit this mold by design.

I find this more unfair when I realize that the “balanced eating” aspect of my newfound lifestyle means eating mostly legumes and soy products, leaving little room for anyone who isn’t a tofu-loving nut to find joy in this exercise of restraint.

It makes me feel like this: I never want to eat again, and yet I simultaneously crave a giant bag of chips.

I am at least somewhat convinced that this specific reaction is an American phenomenon, as the United States conditions its residents to seek food — particularly fatty or sugary foods — as comforts to ward off misery and boredom.

As an unofficial expert in sadness-eating, I can verify that this method very rarely produces the desired results, particularly if one is warding off feelings about the shape of their body.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the United States wastes almost 300 kilos per capita of food per year, more than the net food production per capita of some countries. What food we do eat is mostly fats, sugars, and sodium, with very few vegetables or other foods with significant nutritional value.

But this is all old news.

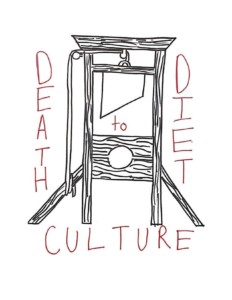

We’re aware of the problem, but we still can’t solve it, in part because its causes go beyond our own nutritional preferences. Societies need individual people to participate in preserving their norms in order to continue functioning in the same way.

That isn’t to say that women can solve our body image issues by changing the way we look. Low self esteem related to body image isn’t straightforward. Once one defect is removed, the mind latches onto another.

If I opt out of overeating, it’s to opt into something much more valuable: beauty, which, as far as I can tell, will make me like myself more and make others more inclined to like me. Why can’t I just buy into it?

Because dieting is shameful, especially for women, as it’s assumed that we’re only doing it for our looks, which is not permissible. Beauty is supposed to come preinstalled, but working towards it is vain and selfish. People who don’t have it shouldn’t start acting like they have it, because they haven’t earned the status that comes with beauty. And while you’re dieting, you’re not participating in the culture of overeating, but you also don’t fit the beauty standard that you’re aiming for.

This is the most disheartening part about trying to change your body: it takes a long time, and while you’re doing it, you’ve temporarily opted out of both norms.

And if you opt out of those norms permanently, what support system is there for you? For all its claims of attempting to diversify the concept of beauty, the body positivity movement is overwhelmingly skinny, white, and conventionally attractive. Leaving a culture of unattainable and racist beauty standards only to enter a culture of unattainable and racist beauty standards in which people don’t carefully cover up their cellulite isn’t the kind of change we’re looking for.

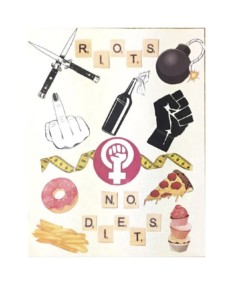

So maybe the only reason we continue to accept this culture is that we have no alternative that is truly pushing for a radical change. In which case, what will make us happy? Compulsively eating large amounts of food, knowing that it will have a detrimental effect on our psyche? Depriving ourselves of food and engaging in vigorous exercise, only for the joy of carefully watching our bodies for any sign that we’re slipping back into old habits?

Do we even want to work for a world that we’ll never see and can’t imagine? What if that world isn’t any better?

Do we even want to work for a world that we’ll never see and can’t imagine? What if that world isn’t any better?

That sounds like a ridiculous question. “Of course that world will be better,” you say! But maybe what I’m most terrified of is acceptance.

If I accept my body, that means that I never get to be any of the things that I’ve waited to be. All of my goals are inextricably tied to my appearance: I want to be a beautiful college graduate, I want to be a beautiful grad student, I want to be a beautiful feminist and fight against societal standards that won’t actually impact me because I will be beautiful. It’s gross, but it’s true.

Achieving my dreams means something much different if I have to achieve them looking as I do now.

We don’t want to resist the structures that make us feel this way, because these structures work in tandem to ensure that there is no answer that will make us happy. Our current situation clearly isn’t working. The traditional American diet is affecting not only our physical health, but our mental well-being.

It is impossible to participate in both facets of society at the same time. But we also don’t want to accept that this is just the way the world works, and that most of us will never be beautiful in a way that translates to heightened social status and fewer unsolicited remarks from strangers.

I’d really love to say “fuck the man” and never worry about my body again. It would just be so much easier for me to do that with a flatter stomach.