Marwa Morgan never intended to become a journalist. But in 2011, while she was studying pharmacy, the Egyptian uprising began.

“I only worked as a pharmacist for two hours,” Morgan joked. Instead, she took pictures of the riots and uploaded them online, where they caught the attention of international media houses.

“That is how a lot of my journalist friends became journalists,” she said.

Morgan shared her experiences as a journalist under Egypt’s authoritarian regime this past Friday at an event organized by the Student Association for the Development of Arab Cultural Awareness (SADACA). Alongside political science professor Jack Paine, she outlined the struggles such journalists endure.

Morgan began by speaking of government antagonism toward independent media publications that criticize them. In countries like Egypt and Algeria, where independent publications still rely on government-owned press machines, she said it was not uncommon for governments to refuse to print issues that painted them in a poor light, or to confiscate newspapers after print.

“In 2015 in Sudan, agents confiscated print runs [from] 14 [publications] on the same day without explanation,” Morgan said.

Both she and Paine spoke of the vital role of social media in countering authoritative regimes, using the Arab Spring and recent protests in Sudan as prime examples. Social platforms, Paine said, can “ignite [a] movement, allowing activists to connect and circumvent the state-controlled media.”

But social media also presents opportunities for dictators.

“Once governments learn to harness social media, it can be used against citizens,” Paine said. He further elaborated on authoritarian regimes’ ability to censor the internet by blocking websites and making VPNs costly.

Morgan echoed Paine, stating that, “Egypt has over 500 websites blocked, including more than 90 news outlets [..] critical of the Egyptian government.”

This persecution is not always confined to the business world. Morgan recounted instances of governments targeting individual journalists through cyber-attacks, online threats, and even fabricated charges, all in an attempt to maintain their international image. She also talked about countries arresting journalists only to later release them, as an intimidation tactic.

“In Egypt […] if you publish information different from the government, that’s considered fake news punishable by prison or fines,” Morgan said.

A report by the Committee to Protect Journalists indicates that as of 2018, 251 journalists were imprisoned worldwide.

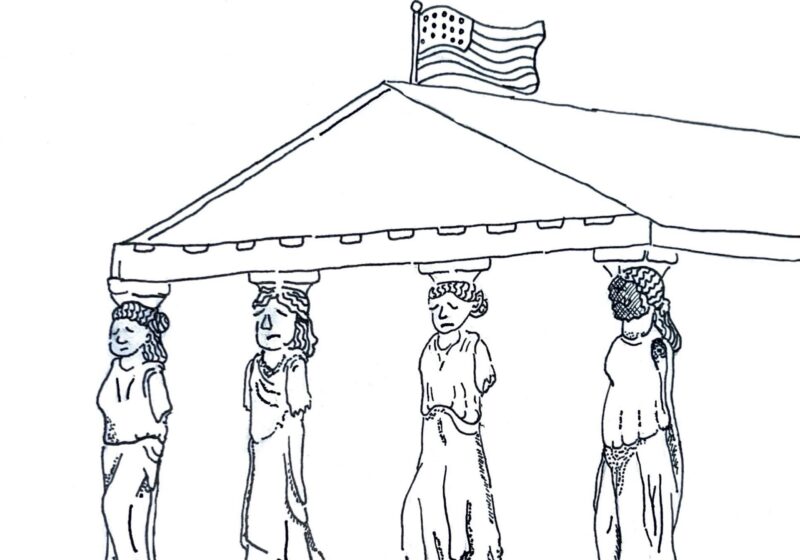

Morgan also touched on the role of the West as suppliers of the surveillance tools used by authoritarian regimes, giving examples of the United States to Egypt, and France in Maummar Gaddafi’s Libya.

“[There are] no laws preventing purchase of surveillance software in cases where it’s obvious they are going to be used by the government against the people,” she said.

Morgan and Paine’s detailed explanation of repressive government techniques left SADACA president and junior Aya Abdelrahman — who is Egyptian — concerned.

“Honestly, after the event I am more scared to pursue journalism,” she said.

But Abdelrahman said she admired Morgan, whom she characterized as “the embodiment of the personal stories of all journalists around the world suffering under oppression.”

Junior Amro Bayoumy left the event hopeful.

“Change takes a lot of time, but it’s always there and it’s always possible,” he said.

In her concluding remarks, Morgan warned the audience not to take the number of imprisoned journalists lightly, highlighting that some are not captured by statistics.

“They are humans who actually lost their freedom or lost their lives and have kids who are growing apart from them and […] families that they haven’t seen in a long time,” she said. “It’s really important to remember that.”