Instead of having friends when I started high school, I played around in Google Earth.

When you’re starting to leave childhood behind and are terminally unsure of yourself, exploring the world from a safe distance is empowering and comforting. Google Earth was colorful, expansive, safe, and as models of buildings became more widespread, occasionally even three-dimensional. There was a sun that moved in real-time and a spectacularly unwieldy flight simulator. I spent hours seeing how fast I could get the plane going straight down, how close to the ground I could pull out of the dive. My parents, bless them, said nothing.

The world outside kept turning, and eventually I caught up to it. I started running and was suddenly good at something socially valued. In a matter of weeks, I was fit, confident, and aware of a physical world beyond my house and school. Each route conquered, each loop to and from my starting point, gave me a new piece of the world to explore.

Google stopped updating Google Earth regularly, and it became buggy and weirdly unpleasant to look at. I didn’t care — I’d stopped using it. I was in and of the real world now.

For the most part, at least. There was one run where I saw a white Prius with some sort of scaffolding affixed to its roof — the Google Street View car. By now Street View had surpassed Google Earth as the major geographic service the company provided. While I didn’t use Street View nearly as much as I had Earth, I still found the basic idea — a constantly updated, 360-degree, first-person POV map of everywhere a (terrifyingly powerful and almost certainly evil) corporation has been able to get its cars — revolutionary. I stopped running and waved.

The car got closer. I waved and waved and waved until suddenly I realized that my Google Street View car was actually just a Prius with a white bike fastened to the top. The driver, looking more than a little confused, waved back.

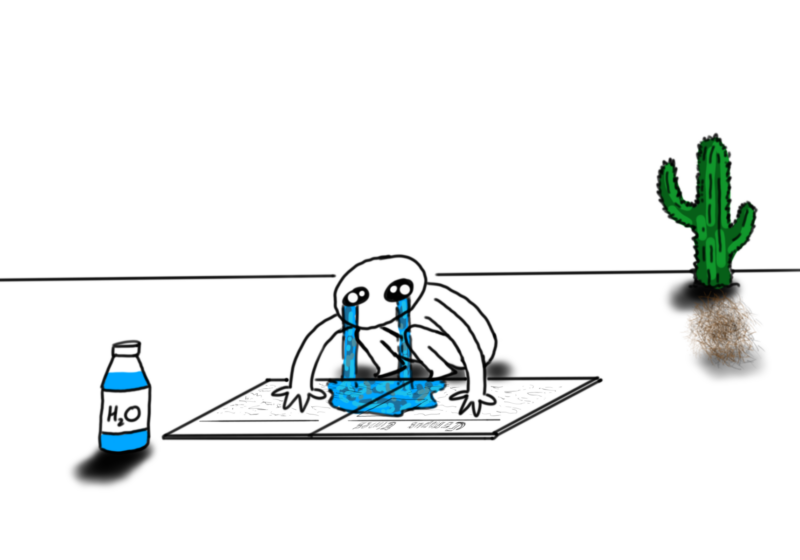

I graduated, came to Rochester, lost my way, and stopped running. It turned out that the real world was full of smarter people, faster people, kinder people, all of whom were already reaching goals I didn’t even know I was supposed to be aiming for. My academic standing became what one would call “precarious,” my body rejected the stress of training and tore itself up, and I spent the summer washing dishes and listening to my boss talk about how Trump would solve everything.

In the Hero’s Journey, this is what’s known as “the abyss.”

And even then, when I was overwhelmed by how little of the world I seemed ready for, I hungered for it. I started reading — big, performative books with endnotes and themes I didn’t understand, but less pretentious things, too. I read Jon Bois’ online novella “17776,” wherein a trio of sentient satellites look down on a world where no one has aged or died in 15,000 years and everybody plays football on a trans-continental scale, and was amazed to find that the majority of his illustrations and graphics were ripped straight from Google Earth. There was art to be made out of something I’d thought of as a childish security blanket. I started writing, and I haven’t stopped yet.

Thinking about Google Earth got me thinking about my encounter with the faux Street View car. I’d waved because I wanted to be documented as aware, aware of where I was and of who was viewing me. I wanted to be documented as having complete control of myself.

That’s a kind of power that is dangerous and ultimately unattainable. Dictators get drunk off that power. It’s also the opposite of what Street View and Google Earth represent. These aren’t tools for conquering the world, but for dreaming it. Before I was ready to join the real world, I could watch it from afar.

I’m doing better now, in school and in life. When I find myself thinking about what I want to achieve and dreading the thought of falling short, I go on to Street View. I find the address of whatever grad school I want to attend or the office of whatever literary magazine I want to write for, and I remind myself that at the end of the day it’s just a building full of normal people, and that the door can be open for me, too.