Our two-party political system is a polarizing force. Disagreements between liberals and conservatives frequently extend beyond impersonal political opinions, provoking emotional responses. Those with dissenting opinions can be judged harshly by their peers, which can make a political conversation turn to personal attacks.

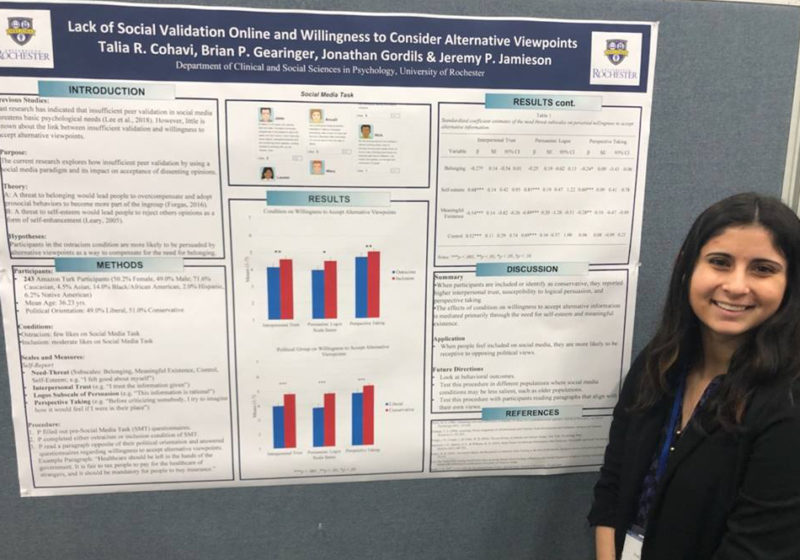

Talia Cohavi and Brian Gearinger, seniors in Jeremy Jamieson’s Social Stress Lab, predicted that people would respond differently when they were the minority versus the majority. Cohavi and Gearinger used a fake social media site to model either inclusion or ostracization through simulated online users, and then evaluated subjects’ willingness to accept political opinions opposite of their own.

A group of 126 conservatives and 117 liberals from across the U.S participated in the experiment online. Each subject created a social media profile, with an avatar and biographical blurb. Then a faux buffering window would tell them that they were being connected to other users, who would either like or ignore their profile. To make the process more realistic, the subject was given three minutes to like other profiles. Half the participants — the “inclusion” group — got many likes. The other half — the “ostracism” group — received very few. In this way, Covhavi and Gearinger simulated peer acceptance and validation as their experimental variable.

After viewing how “liked” they were by peers, each participant read an article — contrasting with the subject’s political affiliation — on either gun control or health care. Conservatives read a liberally charged article, and vice versa. Then, a survey gauged their acceptance of this dissenting opinion.

In general, those in the “ostracism” condition tended to be less open-minded towards the differing opinions. This finding was contrary to their hypothesis. They had thought ostracized individuals would strive for acceptance and be more likely to conform to an opposing stance.

Conservatives were more accepting of liberal readings than liberals were of conservative ones. The readings may have provoked liberals to dissent, despite facing the consequences of being ostracized for their controversial opinion. “The conservative paragraphs threatened the needs of liberals to imitate the ostracism condition,” Cohavi said.

They presented their work last week at the Annual Convention for the Society for Personality and Social Psychology in Portland, Oregon.

Politics has been a theme of several studies Cohavi has been involved in, and she intends to continue exploring how psychology influences politics.

She will graduate this year with a degree in BCS and psychology and a minor in Hebrew. She aspires to be a social psychologist, possibly continuing academic research and teaching. Alternatively, she is also considering research in industry.

First, Cohavi plans on taking time to gain more experience. She aims to work as a lab manager next year. “I’m interested in so many things,” she said. “I want to solidify what I’m interested in before going to grad school, so I can go in with that passion figured out.”

Cohavi urges students to stay open minded and capitalize on Rochester’s curriculum by engaging in academic research. “Push your boundaries and explore.”