Are you there, financial aid office? It’s me, Ashley.

Let me get right to the point: This is about money. That can be a hard thing to talk about, and not everyone likes to do it, I know. Maybe you don’t like to do it either, and that’s why you answer all my questions with the simple yet evocative, “Take out more loans!”

“Loans” is a nice substitute for “money you and your family clearly don’t have, but we don’t care because we were called a ‘new Ivy’ so now we have to raise our tuition every year so people think we’re better than NYU,” or maybe “money you’re going to owe banks until you die because your current projected debt is three times the national average for 2018 ($37,172), but we don’t care because the iZone is an entrepreneurial space.”

It’s a good substitute. I like it.

Presenting you only with cold facts is something that’s been done before, but it doesn’t seem like it affects you much. Instead, I just want to tell you how it feels to be here, as a student, feeling the weight of you not caring.

I’m currently a sophomore and double majoring in Brain and Cognitive Sciences and American Sign Language. I’m minoring in English, workshop-leading for Linguistics 110, and working as a secretary in the ASL Office. I feel rooted.

I’ve been on the Campus Times staff since last semester, and being on it, I’ve discovered people that have reshaped not only my experience at school, but my broader experience as a young adult figuring things out. It’s invaluable. I love it.

My family is struggling financially. My mom is the only one actively working, babysitting, and tutoring disabled children from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. She makes minimum wage, takes care of my little sister, cooks every meal, and cleans the house alone. She’s my whole world and she does everything.

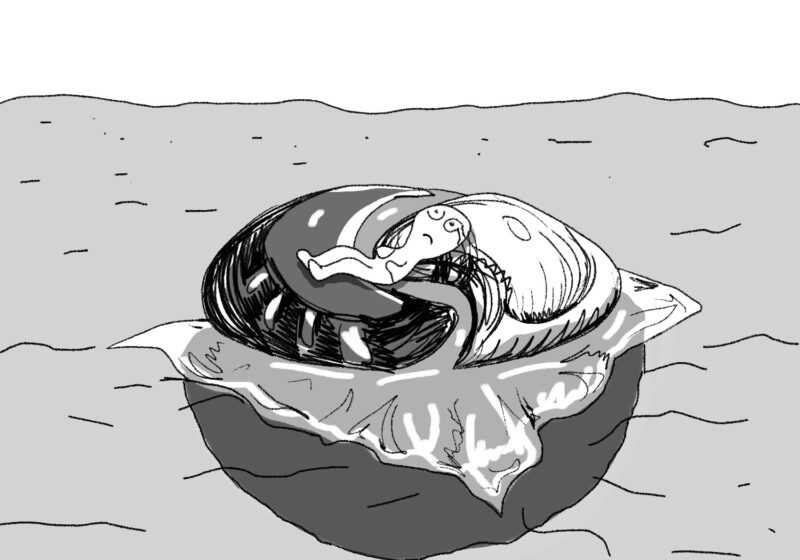

None of that’s enough. My family’s expected contribution is higher than my household income, and when I look at loan statements and the little cluster of numbers indicating their enormity, I feel like everything’s collapsing.

I’m expected to contribute to my family income, and I’m expected to pay them back. I have to go to graduate school, but what if I can’t find a job? What if I can’t find a job that would ever pay enough? What if I can’t handle the stress? What if my therapy doesn’t help?

Why the hell didn’t I go to a SUNY?

These questions seem interminable, and the answers are nonexistent. They rely on a series of maybe’s, if’s, then’s, and other things that no one will really know until they happen.

What feels definite to me is the fact that my school doesn’t care. And that my transfer applications have already been sent.

When my friend Victoria, who is also faced with the great “Financial Transfer Question”, meets with the Director of Financial Aid, Samantha Veeder, she’s told that she can’t expect to be given special treatment. She’s generalizing the financial aid office, she’s making it too personal.

Maybe the financial aid office doesn’t take the financial well-being of its students personally enough.

You’re taking me from a place that’s special to me. Not only a place, but the people in it — my friends who love me, my half-finished major that I have pursued, hungrily. The exposed brick of my favorite building, Lattimore, blooming with slender curls of ivy. The way I feel entering Rush Rhees, internalizing its cream-colored, wanting vastness.

All gone.