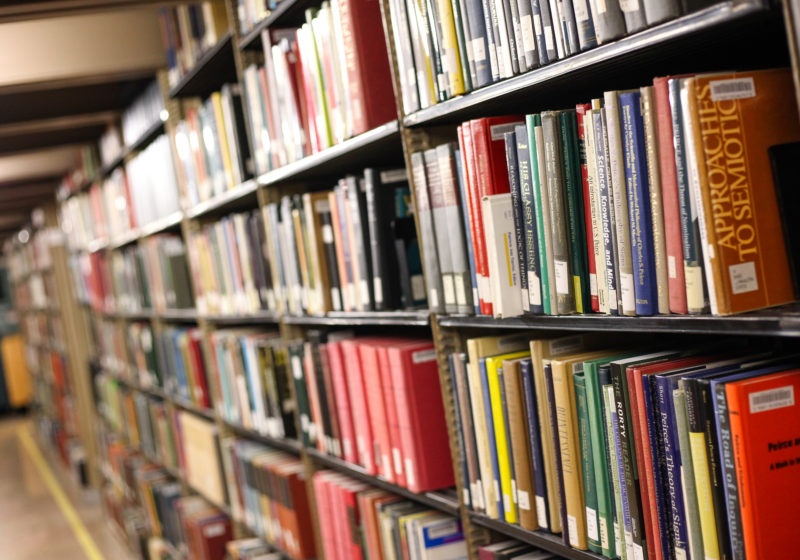

Ever heard of Mark Risjord’s “Woodcutters and Witchcraft: Rationality and Interpretive Change in the Social Sciences?”

No?

What about Suguru Ishikaza’s study of the efficacy of various forms of digital communication, “Improvisational Design: Continuous, Responsive Digital Communication?”

Who, you might ask, actually reads this stuff?

The answer, it turns out, might be nobody. These two books are among the 47.6 percent of books in circulation at UR (about 1.28 million—more on this later), excluding those held at the science libraries or the off-campus annex, that haven’t been checked out in the last twenty years.

47.6 percent!

“That sounds like a lot,” admits Jennifer Bowen, Associate Dean for Scholarly Resource Management. “But it may be deceiving.”

Bowen oversees several key library arms—collections and acquisitions are under her purview, as is the library metadata department—and in her 28 years at the University, she’s worked to better shape its ever-growing collection of books, both physical and digital. (The University added 13,145 books in 2016 alone.)

And though only 52.4 percent of the books (digital and physical) available for checkout in Rush Rhees have recorded a check-out in the last 20 years, there isn’t any data for check-outs prior to 1997, when the University first implemented an online catalog that provides statistics on check-outs.

And given that new scholarship usually sees most of its activity in the first ten years after its been released, it’s possible that some of those that haven’t been checked out in the last twenty years may have been a hot commodity at one time. Additionally, that check-out number can’t account for how many times a book has been taken off a shelf to be referenced, but never brought to the Q&I desk to be recorded as checked-out.

But even allowing for those factors, could they even account for another five percent of books? Ten, if we’re generous? That raises a lot of questions. What’s the utility of a collection that only gets about half used?

“Couldn’t the school’s money go to better use other than buying books nobody has ever even read?” asked junior Dan Levien.

That’s a big question—is this a waste of money?—but the bigger question behind that, of course, is about the utility of knowledge that no one ever accesses.

It depends on what you view as the role of libraries. Bowen, for instance, counts preservation as a major part of a library’s purpose.

“Libraries really feel like there’s a mission to preserve our cultural heritage,” she said.

UR belongs to a group called Eastern Academic Scholars Trust—EAST—that tries to accomplish exactly that, collaborating with other university libraries to determine how unique their collections are, and which books are duplicated across their shared system.

In addition to the preservation aspect, there’s the “serendipity of discovery,” as Bowen puts it. For students stuck on a paper or humanities professors looking for research topics, the unexpected is always just sitting on a shelf somewhere, waiting to be discovered, regardless of its accessibility.

Which is, of course, something that’s bound to happen in a searchable collection of 1.28 million volumes.

As for the mythical “over 3 million volumes” refrain from some adventurous Meridians (including yours truly), if there’s any truth to it, it would include the Physics, Optics, and Astronomy Library, Robbins, Koller-Collins, Carlson libraries, Rare Books and Special Collections, and the off-campus annex in Brighton, which houses over 400,000 “older or lesser used” books and printed journals.

For now, University librarians are busy studying a 383,000-volume “base” that they’ve pledged to include in the EAST project. After that, they’ll start to analyze any overlap with other EAST schools to determine the best way to store and preserve those books.

But in the mean time, “Variability in Grain Yields: Implications for Agricultural Research and Policy in Developing Countries” is just sitting on Level 3, waiting for someone to take it off the shelf.