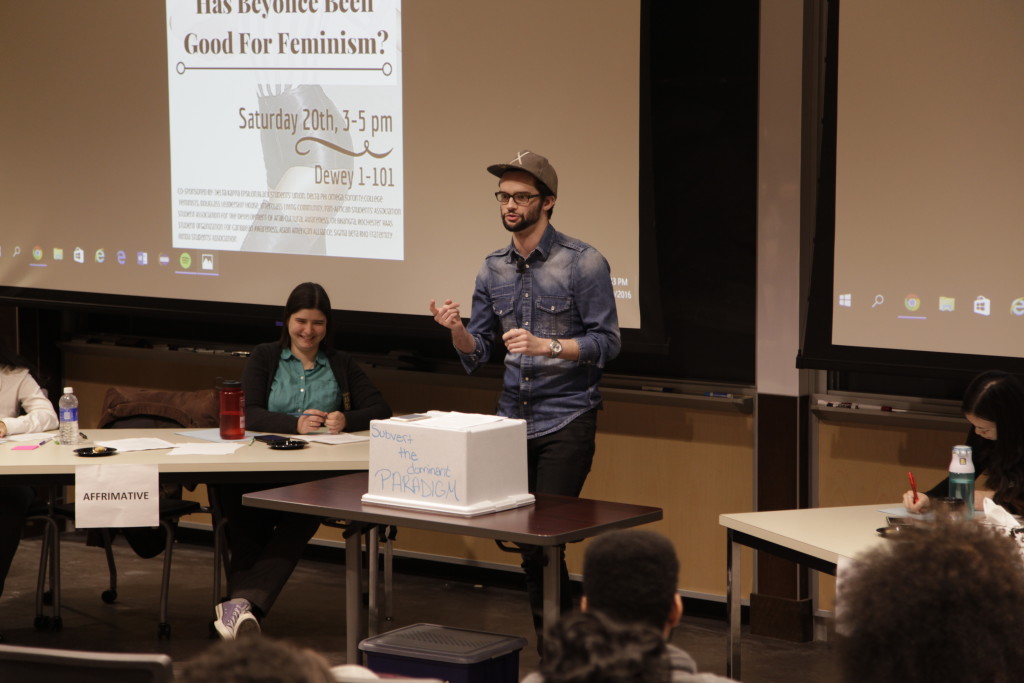

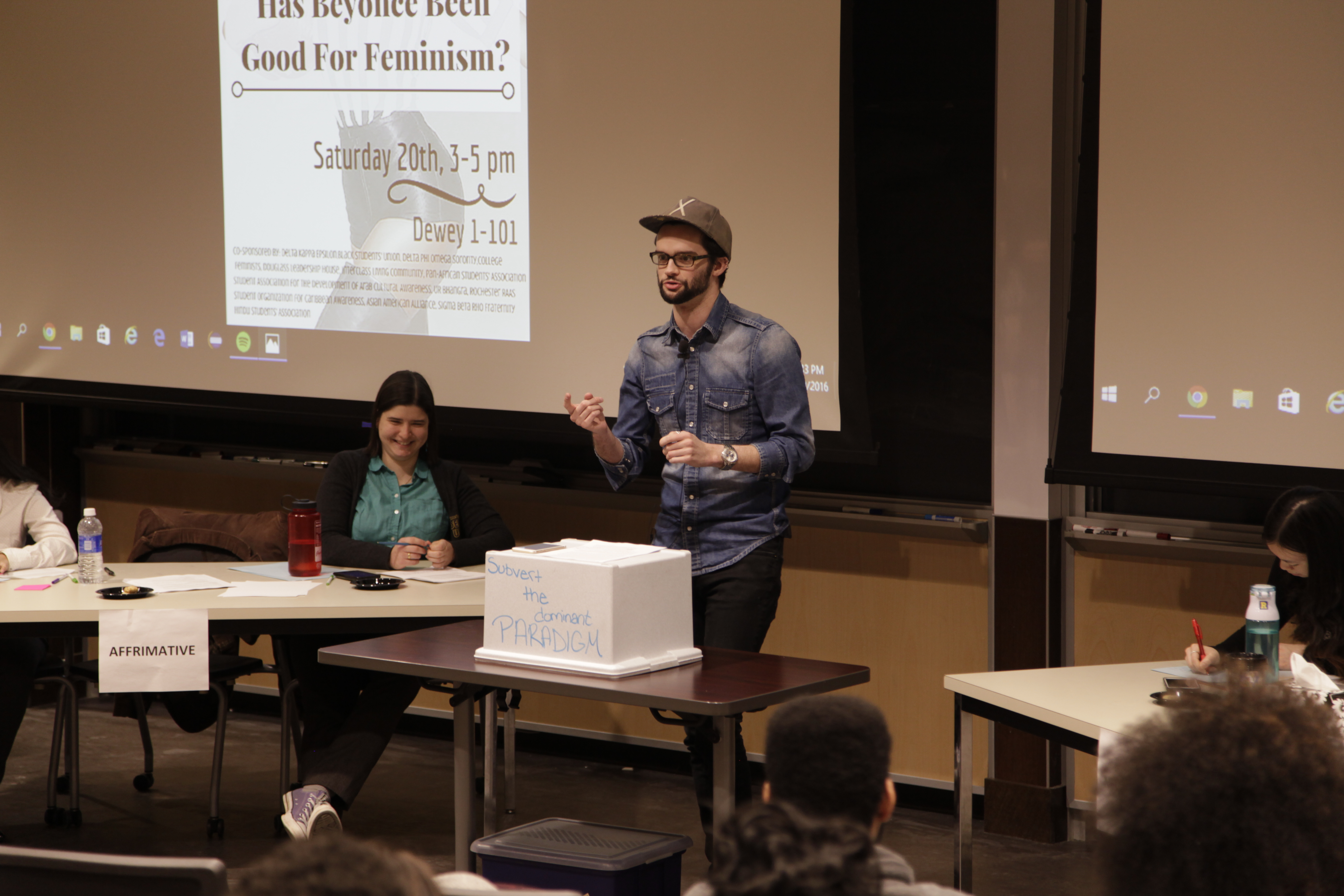

Has Beyoncé been good for feminism? The UR Debate Union tried to answer this question Sunday in its annual spring public debate. The debate lasted for almost two hours, and included an open floor at the end for the audience members’ perspectives.

On the affirmative side were junior and Debate Union Vice President Miriam Kohn, sophomore Graeme McGuire, and freshman Elizabeth De Los Reyes. Meanwhile, arguing against Beyoncé’s impact on feminism were sophomores Benjamin Frazer, Naomi Rutagarama, and External Publicity Manager Anne Cheng.

Most of the debate revolved around the accessibility of Beyoncé’s feminism to the female population. Kohn, speaking from the affirmative side, addressed this concept and noted that, “It’s not fair to hold [Beyoncé] to the standard of representing everyone, but she’s making sure she allows women of color to participate in discussions [regarding feminism].”

Kohn also went on to explain how Beyoncé, through presenting her culture—by alluding in her new “Formation” music video to the Black Panther movement and police brutality, and referencing “out of sight, out of mind” issues like Hurricane Katrina—pushes people to take notice and “prompt[s] discussion of [an] issue that’s typically swept under the rug.”

Cheng, from the opposing side, argued that Beyoncé doesn’t talk about experiences relevant to everyone, which excludes some groups of people. “She perpetuates a form of feminism that doesn’t consider intersectionality, which hurts the movement,” Cheng said.

Cheng also argued that Beyoncé tells women they’ll only be respected if they present themselves in a manner similar to her own, saying, “the [“Partition”] music video depicts her dancing on a pole wearing next to nothing. This completely undermines Beyoncé’s other songs by literally saying that she dresses and acts the way she does so that a man will want her.” Cheng added that Beyoncé is subjecting herself to patriarchal standards, and therefore sends out a message that “women should sexualize themselves to get men.”

Rutagarama, who was on the same side as Cheng, argued that the inclusiveness of feminism shouldn’t be limited to the experiences of just one group of women. Rather, she said, feminism should include the experiences of women who are capable, strong, independent, and even vulnerable.

In her argument, Cheng pointed out that the definition of feminism Beyoncé seems to adhere to is watered-down compared to the feminism talked about in academia—it doesn’t fully showcase the roots of the movement and the construct through which it came to be. In response to this, De Los Reyes agreed that Beyoncé doesn’t give an academic definition of feminism, but argued that “Beyoncé has to enforce feminism as she stands for [it].”

De Los Reyes also noted that the reality of feminism cannot be constituted as a “one-size-fits-all problem,” because that would mean fitting into the mold of the majority: white women. Teammate McGuire agreed, saying that all women do not share one and the same experience. “She doesn’t cater to everyone because nobody can,” he added.

Frazer, in his dissent, included a story about two slam poets, Natasha T. Miller and Siaara Freeman. In their ongoing “Good Grief” tour, the poets had shared an encounter they had with one of their white feminist friends. When Miller and Freeman were mourning the death of their father, seven years after his death, their white friend chastised them, saying, “What would Beyoncé do? She would be fierce.”

Though this cannot be a “one-size-fits-all” problem, Frazer argued that the narratives surrounding white and black women are too different. White women, he posited, are expected to be the image of domesticity, while black women are characterized as hypersexual and primitive—characteristics stemming from a history of oppression.

Through the story, Frazer highlighted Beyoncé’s “complicity.” He added that, because of Beyoncé’s star power, she is able to expose women everywhere to black feminism—and that, more often than not, Beyoncé provides women’s only exposure to black feminism.

“To [white women], Beyoncé’s feminism is about strength,” Frazier said. “In this case, having a black pop idol speak loudly and most often about dominant narratives that most commonly affect white women has allowed white feminists to conflate those narratives that are structurally oppressive towards black women,” he concluded.

At the end of the debate, students in attendance had one minute each to voice their opinions on the floor. One student brought up the new Coldplay music video, “Hymn for the Weekend,” in which Beyoncé sports an Indian sari and henna, which the student thought added to the exotification of South Asian women. “If you’re adding to exotification and also associating with someone who excludes narratives of other people [Former UFC Champion Ronda Rousey],” the student said, “then I would argue that you’re not good for feminism.”

Argument after argument, comment after comment, the debate focused on Beyoncé’s “black feminism” and how white and black women respond to it. The room was engulfed with the sounds of knuckles rapping on wooden tables and people cheering, after sophomore Alexandria Brown asked, “We’re talking about black and white feminism. Where the hell is everyone else?”