A man, Matt, and his wife, Wilma, discuss with their son where he wants to be buried. Does he want to be next to his sister, Meredith, for all of eternity?

“Gross,” the son says. Fine. He can be buried between his mother and father.

“But wait,” the man says. “That won’t work.”

Why? Because his son’s name is Damon. Matt, next to Damon. Matt. Damon.

Meredith, the daughter, walks in, just stopping by. She hurries out again, having forgotten something in her car. She returns with her new husband, Chuck, who thinks his wife is “so conformist” for calling her parents “mom” and “dad.”

“This complicates things,” Matt says, now having to consider a fifth burial plot. Also, no one wants to be buried with Chuck. The scene ends with us realizing that this family, particularly Wilma, will do anything—actually, anything—to have her family buried in the order she wants, keeping herself far from Chuck.

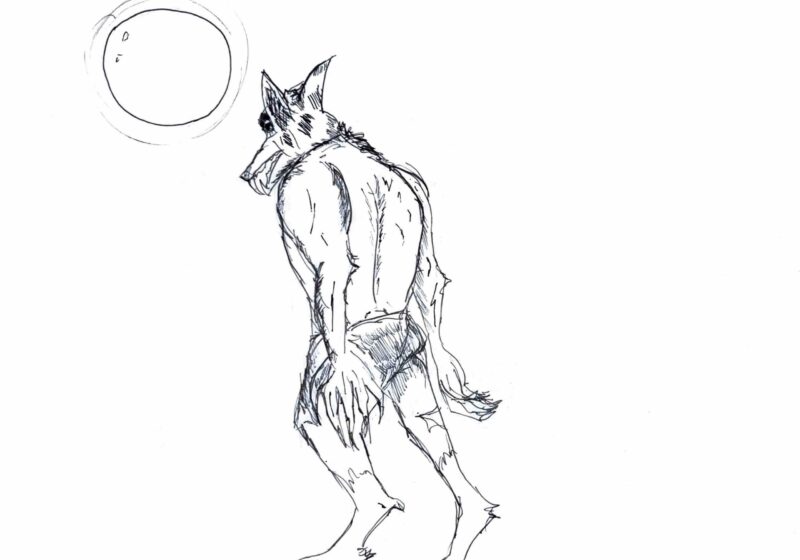

A bat flaps around the rafters of a dilapidated chapel in Mt. Hope Cemetery as a young man compares himself to Batman. He is terrified of bats. Yet, he wishes more than anything that this fear came with the same kind of mystery that Batman emanates. This man and his father are in the process of restoring a cemetery chapel, literally brick by brick. Bricks in hand, father and son cower in fear of the bat, which is still making the rounds. We soon learn from the father that, as it turns out, there is a dark and mysterious family secret—one that explains why bats are so terrifying to him and his son. The scene ends with the son’s ecstasy at learning of this Batman-esque backstory.

Sarah Stout and her brother, Ira, rendezvous secretly in an attic. Ira has murdered his sister’s abusive husband, Charles Littles. The siblings not only share this paranoia-inducing secret, but they are lovers, too, trapped in the potential shame of their incest. Someone knocks at the door. Ira hides, and Sarah’s other brother, Eli, walks in. Through Eli’s conversation with his sister, we realize that this is not an attic at all, but rather Sarah’s apartment, and that Ira couldn’t possibly be hiding in that very room, for he was convicted and hanged for the murder of Charles Littles some time ago.

These three stories were staged readings of short works by the writers in Geva Theater’s third-annual Bake-Off, held this past Friday, Oct. 30. In the spirit of Halloween, the Bake-Off is an event that showcases the works of local writers, presenting them with a topic and guidelines in an event that does not actually involve baking. This year, Bake-Off organizers sent writers on the annual Mount Hope Cemetery Torch Light Tour, tasking them with writing a short scene inspired by the stories told on this nighttime exploration of Rochester’s massive, 177-year-old burial space.

One such writer—who wrote the scene depicting a family sorting out burial placement—was UR’s own Katherine Varga ‘T5, who also wrote the recently-performed “Energy Mass Light.”

“One of the last things the tour guide mentioned wasn’t really part of the tour—it was a family plot she thought was interesting because the order of the graves had been changed a few times, and was ultimately decided by the last woman alive in the family,” Varga said of her inspiration. “In fact, sometimes orders of graves would be changed even after the bodies were buried.”

What was most fun about attending Geva’s Bake-Off was the audience involvement—casting for these scenes occurs on-spot, with audience members volunteering to do a raw, unrehearsed reading of the scene. There was also an open bar (to facilitate this participation, probably) to which audience members were welcome between performances.

“I loved the idea of rearranging graves, and thought it would lead to some amusing situational humor,” Varga said—and that it did. I experienced the physical humor of this piece firsthand, having been chosen to participate as an audience reader of Varga’s scene. (I played Meredith.) As the husband and wife deliberated where their children and new son-in-law should be placed “for the rest of eternity,” each person moved on stage in the order in which they might be buried. Shuffling around on stage while reading from Varga’s script, especially considering the fact that the actors were also experiencing the movement for the first time, produced quite a laugh from viewers. What’s more, Varga’s choice to poke fun at the care people place on what is, essentially, buried life-after-death, was morbidly hilarious.

Also amusing was the piece on the bat-fearing, chapel-restoring, father-son duo. Written by Geva Literary Director/Resident Dramaturge Jenni Werner, the scene was a vivid presentation of a quirky and dorky man obsessed with superheroes. Even in the absence of staging, props or any sort of practice, the stage directions (read aloud during each performance) painted quite the picture. Holding an invisible brick in his hand, the person acting as the son read his lines fluently and with spot-on timing, executing the character’s preoccupation with mystery with a surprising clarity. Werner’s writing also left me wondering, after so much build up, why these men were so terrified of bats. The open ending left the work on a dramatic note, which was previously unexpected considering the light-heartedness of the protagonist. According to Werner, the piece was inspired by a part of the tour where they went inside an old chapel and listened to an actor pretending to be Jacob Gould, the second mayor of Rochester, while a bat flew around overhead.

The last piece I summarized veered away from humor into a tragic depiction of the notorious tale of the Stout family murder trial. The tale is commonly known for the incestuous love affair between Marion Ira Scott and his sister, Sarah, and their failed attempt to push Sara’s alcoholic husband off a cliff into High Falls. The murder was poorly-executed, with the body landing on an edge, which led to Ira’s hanging and burial in Mount Hope Cemetery. What is refreshing about the scene performed in the Bake-Off is its sympathetic depiction of Ira and Sarah. The writer of this piece, Emma Milligan, told us she wanted to look at Sara and Ira from this different angle. She certainly succeeded. Ira called Sara “chicky” as a term of endearment, and expressed his hatred and anger towards Sarah’s late husband, who had been so cruel to her. After Eli leaves, and Ira comes back out from hiding, Sara is terrified—perhaps most depressing is her lucidity in the end—if only she could revert back into the madness her delusion displays, she could be happy. But, the scene ends with Sarah’s doubt and fear, and we see her story for what it is.

These are only three out of the eight works featured at this year’s Bake-Off, all of which were enjoyable. Other plays featured scenes including Fredrick Douglass, Susan B. Anthony and former Mayor Gould, which were informative through their amusing and extensive accounts of Rochester’s history. One play took a similar route as Milligan’s, focusing on an individual’s sorrow. It was a somber depiction of a man who had committed suicide and consequently been buried outside his wife’s family mausoleum. This scene constructed a beautiful metaphor, one that was not clear until the writer explained the story of the separate burials.

In it, the man is sitting alone. A woman joins and they discuss missing each other, but for some reason we only know that he just “had to go.” There is an indefinable gravity within their sparse, unrevealing dialogue. We get the sense that they were so close in life that they could understand each other without much talk. Knowing afterwards that these people were husband and wife, separated by suicide in life and in their burials after death, we can deduce that the scene is taking place in an after-life sort of space. The husband tells her as she leaves, “I’ll be here,” and we are forced to assume he means his grave.

The Bake-Off event was inspired by Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Paula Vogel, who wrote the famous “How I Learned to Drive.” It has been held as a part of Geva’s Festival of New Writers for the past three years.

McAdams is a member of the class of 2017.