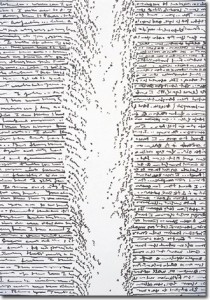

Courtesy of tayoheuser.com

I had this teacher in high school who used to tell my English class that to revise any piece of written work it was essential to go through it word by individual word and ask why that specific word was there. What precise function does it serve? Why choose antiquated instead of dilapidated and what effect does that choice have on the piece as a whole? How does the second sentence of the paragraph follow from the first and is the connection clear enough to someone who isn’t privy to the esoteric workings of your own mind? Why that word? Why that paragraph break? Why that comma? Why, why, why?

At the time, the advice struck me as singularly depressing. Revising my work word by word struck me as an endeavor not unlike reading “War and Peace” and sent me into a spiral of mania in which every word I analyzed conjured up a flurry of other possible words and left me with sheets upon sheets of paper covered in my frenetic cursive while I wondered how it could ever be possible to settle on a perfect word. Gustave Flaubert’s words echoed in my head with demonic mockery: “There is no such thing as a synonym, there is always a perfect word.”

As I go further into the world of journalism with the buffer of a lot of years of terrible writing, I find myself returning to my teacher’s advice more and more. One word of a misstep in a news article can leave me the unfortunate recipient of a slew of angry emails from people who feel everything from personally offended to deeply sad to wanting my head severed, often justifiably so.

Why did you choose to say that students “admitted” rather than students “said,” critics will ask. Are you trying to imply that students are guilty of something? Why are you disseminating such inflammatory rhetoric? Why did you choose to insert the qualifier “slightly” in front of disillusioned when I explicitly said I was disillusioned with the movement? Why would you call the crime “notorious”? Is it true or isn’t it?

All of the above situations are true, by the way, and are only a small snapshot of the difficulties I’ve found in choosing the right words to tell the stories I want to tell without offending, without misrepresenting and without being biased. But all of this isn’t meant to attempt to absolve myself of blame for situations in which I undoubtedly deserve it — my word Purgatory is self-imposed, I know.

What it is to say is that ethics and journalism mix strangely. Earlier this semester, a professor contacted me to express extreme discontent with the quotes I used from our interview for an article on cheating and wanted to know about the ethics of revising the article online. The quotes I used were accurate, I told her, and although the issue is immensely nuanced, I had to leave out things from the interview because it’s an article, not a thesis statement. Before that, it was brought to our attention that printing a student’s name in connection with a criminal charge in our Security Update hadn’t been strictly wrong, but perhaps wrong in a moral sense, and yet as a newspaper we have the unfortunate characteristic of being unable to undo anything — your mistakes are there, paraded out in a neat line of newsprint for time immemorial.

Life never has an instruction manual when you need one, and in journalism I always feel that this reality is pronounced. People I talk to in the wake of mistakes want answers, they want me to enumerate non-existent policies in black and white, but instead all I can offer is discussion, theories, my own inchoate experiences, apologies that are sincere but sound obsequious and, ultimately, my own decision. And sometimes I’m wrong. Sometimes it’s the wrong word. Sometimes what’s heard in an interview isn’t precisely what was said because we’re different people approaching the world from the vastly different spheres of our own experiences.

But none of that means that you shouldn’t trust someone because they have the vantage point of being the one fielding questions, not scrambling to compose an answer. It means that you should be upset or offended if it’s warranted, but also be forgiving when it’s warranted. It means that interviews shouldn’t be about perfectly articulate answers. You can’t ever get at the truth by reading a script, just like you can never write the truth if you’re too entrenched in the fear of being wrong.

Jack Kerouac said on writing that, “one day, I’ll find the right words and they’ll be simple.” Even if Kerouac never found them, he wrote anyway, hoping to, writing what was real, groping for some truth, somewhere. Maybe someday I’ll find the right words to tell all the stories I want to tell, to have all the conversations that could be had, to bridge all the gaps between people I wish could be bridged, to write all the imagined realities that could be brought to life.

Someday, right?

Buletti is a member of the class of 2013.