In their June 1891 issue, UR’s student newspaper at the time, The Campus, declared their opposition to the entry of women into “this most sacred institution.” Their arguments ranged from “women can’t kick” and “Rochester is it a manly college” to “this is not a matrimonial agency.”

Despite such protests, through the efforts of women like Susan B. Anthony and Helen Barrett Montgomery, the University finally opened its doors to women at the turn of the 20th century. Although women were previously allowed to enroll in University courses such as English literature and chemistry during the 1870s, the first female cohort was admitted decades later in 1900.

Despite matriculation into the University, female students were actively shunned by the male students, encountering shut doors to classrooms and blockades on stairways. It wasn’t until 1910 that women received their first yearbook, the Croceus, which was dedicated to Susan B. Anthony. Some 15 years later, the first issue of The Cloister Window, the first College for Women newspaper, was published.

Not to be confused with the literary magazine Cloister, The Cloister Window sought to document the activities of the female student body with “some semblance of freshness.” Filled with determination, the first editors of The Cloister Window aimed to prove the livelihood of the Women’s College: “where it has been felt that the happenings are insufficient. ‘The Cloister Window’ is to be our proof against this assertion, by printing what really does happen.”

Earnestly, they encouraged their peers to send in constructive criticism, looking forward to the evolution of the paper in years to come.

Under the leadership of Margaret M. Frawley, The Cloister Window was first published fortnightly (weekly, starting 1926) including sections on college news, alumni updates, a collection of literary parodies, letters, and riddles, “Truth and Consequences,” and the opinionated “The Reflector.” As its name suggests, “The Reflector” accrued anonymous letters from students, provoking much discussion and debate on all different kinds of subject matter.

For instance, in the Oct. 23, 1925 issue, one progressive-minded student stressed the importance of citizenship, which meant engaging and staying informed about politics. They suggested a monthly political forum for students to participate in and “be properly trained in such matters.” In a similar vein, another student raised the issue of fraudulent Students’ Association elections. Pointing to the flawed vote-counting system, they proposed a new set of precautions or voting regulations to prevent such suspicions. However, many light-hearted and superficial letters were also published, ranging from complaints on first-year etiquette to praise for keeping the “Junior candy counter” well-stocked.

Although “The Reflector” was discontinued in 1930, the newspaper continued to embody the voices of the female student body, painting a wide landscape of student activities, opinions, and of course, the latest news. Columns featuring letters to the editor remained consistent throughout the entire run of both The Cloister Window and its successor, The Tower Times.

In 1930, the male students moved to the newly-built River Campus. In turn, the female students moved from their original buildings, the Catharine Strong Hall and Anthony Gymnasium, to the Prince Street Campus. The offices of the newspaper were moved to Culter Union, “a tower from which the entire campus may be viewed with perspective,” giving rise to the new name, the Tower Times.

It was also during the Tower Times’ run that the paper’s coverage began mirroring that of The Campus, reflecting growing interaction between the two campuses. For example, for both newspapers’ March 14, 1947 issue, overlapping articles included coverage on the Humanities Conference, a roster of the most recent Panhellenic inductees, and phenomenal reviews on the most recent Kaleidoscope production, “Strikes Me Funny.” In the two Dec. 2, 1949 issues, the front-page articles for both papers were virtually indistinguishable, including content on choosing the new UR president, the underwater-themed sorority ball, and the presentation of Milton at a literary conference.

The overlapping content is not to suggest that the College for Women had somehow lost their independent voice, separate from the male student body. In comparison to The Campus, which emphasized sporting events and athletic recruitment, the Tower Times focused on a variety of subjects, ranging from the international affairs column, “World Events of the Week,” to coverage on the arts such as literary reviews, the Art Gallery, and both on- and off-campus theatre productions.

Particularly noteworthy is “The Lookout,” which was something akin to, but not quite, a humour column. Content was always full of surprises, from snippets of overheard or made-up conversations to humorous observations and witty remarks, from pointing out daisies on Stan Cornish’s work coat lapels to pick-up lines like “Have you heard the Vitamin Song? So Beets My Heart for You.”

Throughout 1943, during World War II, The Campus and the Tower Times temporarily joined together for the first time as the Campus Times, an early indication of what was to follow in the mid-50s. This move raised compliments from Jacob Robert Cominsky, then the President of the Alumni Association of Greater New York. Student reactions towards the sudden merge were mixed, but generally appreciative.

Content on World War II remained relatively unbiased and nonpartisan. A “Question of the Week” on whether America could remain separate from the war represented a variety of views, ranging from isolationist preferences to confident “nos” due to international economic ties. The Tower Times generally took a more liberal stance, publishing a variety of articles concerning the refugee problem. Such articles were mostly in support for opening college doors to refugee students and endorsing campaigns to raise funds to assist these new students.

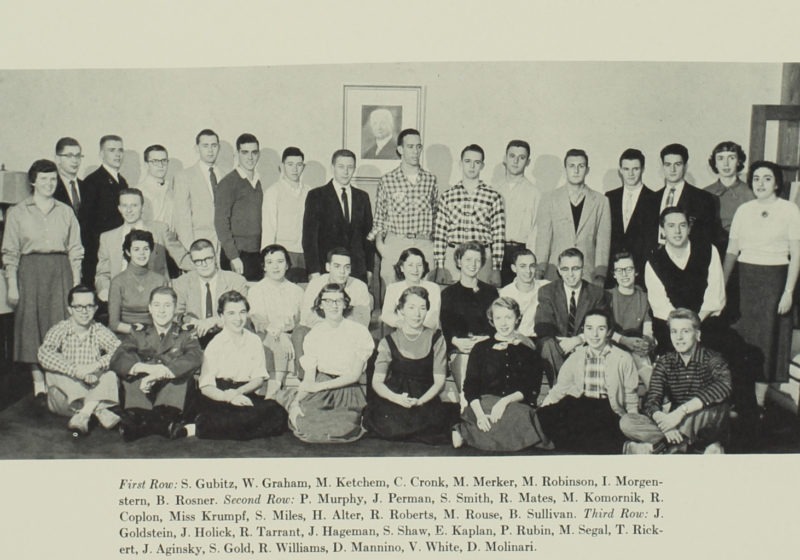

About a decade after WW2, it was decided that the University would merge the two separate campuses, so the two newspapers began consolidating their efforts. The collaborative efforts of The Campus and the Tower Times gave birth to the Campus Times, as students know it today. Originally headquartered in Todd Union, the CT began in 1955 under the leadership of Sarah Miles Watts, the last editor-in-chief of the Tower Times.

Leaving Prince Street was bittersweet, as Watts reflects in her article, “Smiles and Tears,” published in the final issue of the Tower Times.

“We like Prince Street. Working hard in class and in activities, we’ve tried to discover the value of things. Sometimes we weren’t encouraged, sometimes we weren’t recognized, and sometimes we made mistakes or didn’t even do a good job. But we’ve done something, we tried to do our best and we’ve learned a lot.”