Tenure is one of the most important distinctions for professors at any college. It offers guaranteed job security and funding for research.

Originally introduced to the North American collegiate world with the intent of protecting professors with controversial research or opinions, it ensures professors the academic freedom to study and express whatever they choose.

The concept of tenure was officially introduced in 1915 and has since become a standard in North American academia.

At UR, tenure is granted to professors who have made significant accomplishments in scholarship, teaching and service to the University.

The scholarship component is based on assessment of research both by their primary department and by external experts in the field. Through this system, the school hopes to grant the benefits of tenure to faculty members who are dedicated to their research, their students, and to the university itself.

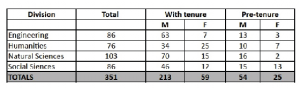

Feminists fighting for gender equality have accused the universities across the nation of discriminating against women both during the hiring process and when granting tenure. As women increasingly gain ground in the world of academia, many more women are able to achieve tenured positions at universities, though the number of tenured women is still struggling to catch up to that of their male counterparts.

This is a battle that continues in the majority of colleges and universities across the U.S.. For example, last month, Rochester Institute of Technology received a grant to increase the number of tenured female faculty in the science, technology, engineering and math fields.

Similarly, UR has a skewed ratio of male to female faculty, especially in the Natural Science departments. In the Chemistry department, there are over 15 tenured faculty members but only two female faculty members.

According to tenured chemistry professor Kara Bren, “The policy does not make any distinctions between men and women… but at U of R particularly the number of women in Chemistry faculty positions is very small.”

This is tragic, especially in a field like chemistry, where tenure allows professors to take real risks with their research that they would have been unable to take in a less-secure job position.

“Once you have tenure, you have job security that allows you to take more risks with your research,” Professor Bren said. “I know that after tenure, I really branched out into new fields and took some chances, some of which have paid off well.”

Because the University grants tenure to fewer women, more women, are in turn unable to pursue riskier research that could potentially yield invaluable results.

However, UR policy makes no distinctions between men and women.

“I know that the statistics in terms of gender for tenured faculty is not great…[but] I was tenured last year, and the process was very smooth for me,” anthropology professor Eleana Kim said. “My time here [at the University] has been unquestionably positive in every sense.” Professor Bren agreed, expressing a positive attitude toward the way the tenuring process is handled at UR.

Provost Peter Lennie said in a private interview that the way tenure is handled here is fairly standard for a U.S. research university, and that the administration “work[s] hard to ensure that junior faculty are well-supported here, regardless of gender.”

Lennie believes that gender is not at all a factor in whether professors here are granted tenure and said that the imbalanced numbers were more a result of the sheer number of men and women pursuing academic careers in each discipline.

This is an issue throughout our society, not one specifically perpetuated by our school. As more young men and women in America are raised believing that they are equals, more women will feel that they can achieve greater heights – both in the academic world and elsewhere. The problem is slowly resolving itself.

For the first time, in 2009 and continuing through 2011, more women were awarded doctorates in the U.S. than men. The current generation of college students is the first in which more women will graduate than men. There is hope that this trend will translate into an increased number of tenured female faculty at universities, including our own, in the future.

Everhart is a member of the Class of 2016.